CARLO FINELLI CARRARA 1782-ROME 1853

Further images

Provenance

The artist to 1853; upon Finelli’s death to Filippo Massani; then by descent to his daughter Anna Massani Camuccini and her husband Giambattista Camuccini, Palazzo Camuccini, Cantalupo in Sabina Italy; then by descent in the Camuccini family to the collection of Baron Vincenzo Camuccini.

Exhibitions

Equilibrium, by Stefania Ricci and Sergio Risaliti, Florence, Museo Salvatore Ferragamo, 19 June 2014 - 12 April 2015, p. 114; DOPO CANOVA: Percorsi della scultura a Firenze e Roma, curated by Sergej Androsov, Massimo Bertozzi and Ettore Spalletti, Cucchiari, Carrara, 8 July - 22 October 2017.

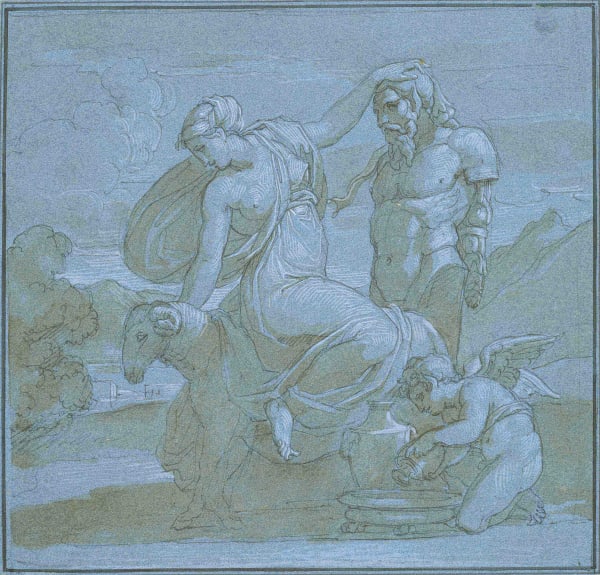

Nineteenth century biographers recorded Carlo Finelli’sconfrontational attitude toward the most admired works of contemporary sculpture, an attitude that often verged on intolerance and outright rejection. Finelli demonstrated his talent from his very first major commission, the frieze representing The Triumph of Julius Caesarfor the Napoleonic apartments in the Quirinal palace. Although Carlo Finelli admired the formal and iconographic aspects of both Canova’s and Thorvaldsen’s art, he sought his own independent style, rejecting the received “rules” informally codified by their great worksand admiredthe art of the 16th-century sculptor Giambologna (Musetti2001, p. 154, Ibid, 2002, p 26 ff).

According to Finelli’s biographer Giuseppe Checchertelli, Finelli developed an eclectic style, a synthesis combining the classical ideal of form withpurity of thought that criticsrecognized in the “primitives” of the 14th and 15th centuries (Checchertelli, 1854, p.13).Yet the gulf between Finelli’s ideal and its realization resulted in episodes such as the destruction of his Mars in 1844, a sculpture he had already donated to the Academy of Fine Art of Florence, that he took back with the excuse of retouching it. The same fate was suffered by a group of bozzetti and other marble sculptures such as two sculptures of Venus anda Paris. Moreover, the artist’slast will ordered the destruction of all the plaster models in his studio with theexception of the Dancing Hoursand the Archangel Michael Defeating Lucifer, his mostrepresentative examples of Christian and mythological genres, both of which he intended to donateto the Academy of Fine Art in Carrara.

Because of these events the strange nature of Finelli’s personality was confirmed to his contemporaries and, at the same time, gave rise to the myth of his independence and genius which, along with his choice of subjects, lead to his comparison with Michelangelo, the “sublime” artist parexcellence (Campori, 1873, p.100).

The comparison between these two artists was advanced especially on the basis of Finelli’s marble group the Three Graces, a sculpture emblematic of his entire artistic fortune. In 1824 after having finished the marble group the Dancing Hours for the Russian Nikolai Demidov (Hermitage Museum, cf. Androsov, Musetti, 2003, Rome 2003, p. 394), Finelli had the opportunity to return to the subject of theThree Gracesthat both Canova and Thorvaldsen had created earlier although in a style much different than Finelli’s version of the “gracious genre.”

After Finelli destroyed his first version of the Three Graces, he made a second version also in plaster that he destroyed in 1833. At that point, he decided to work directly on the marble, “alla prima,” without the guidance of a plaster model. This was a very unusual working method at the time, for there was no room for errors or second thoughts and this unorthodox procedure immediately evoked comparison to Michelangelo’s working method.

However, Finelli never completed this work. It was always hidden from studio visitors and became famous only after his death. After his death, the Three Graces was inherited by Filippo Massani. The Three Gracesis a unique case for sculpture of that period. The sculpture is beautifully finished, apart from the tree trunk and feet that are partially defined. Only the surface of the three figures awaited a final light polish. Probably the group’s history and the absence of a plaster model suggested to Finelli’s heirs and pupils that this was the way he wanted the group to be seen even if this was not the usual practice at the time. Moreover, unanimous contemporary opinion held that the Three Graces’ “non finito” greatly increased its appeal due to the delicacy of style. These factors made it Finelli’s “most perfect” masterpiece.

“E, a vero dire, questo gruppo gruppo è tal cosa che incanta, né saprei giudicare se quelle estremità non finite tolgano più che non aggiungano a quel velo di magia che tutto involge questo lavoro. Vedi le tre donzelle intrecciar leggiadre le braccia senza darsi studio della persona, perché la grazia non ha vezzi fittizi; contempli que’ volti ingenui, quella trasparente serenità di pensiero, ed a buon diritto esclami, senza d’esse niuna cosa, neppur la bellezza aver pregio nel mondo!” (Checchetelli, p.28).

“To tell the truth, one would never say about this enchanting group that the unfinished extremities take away more than they add to that veil of magic that completely envelops this sculpture. One sees the three young damsels unselfconsciously and delicately entwine their graceful arms, because grace is neither false nor affected. One contemplates those innocent faces, that transparent serenity of thought, and one can exclaim truthfully that without them nothing, not even beauty, would be the most highly valued quality in the world!” (Checchertelli, p. 28). Elegant young bodies studied from live models were placed in poses of celebrated ancient sculptures, above all the two figures at the sides. That on the observer’s right assumes the pose of Apollo with theHarp (Rome, Capitoline Museum), with its crossed legs, similar outstretched torso and placement of the arm.

On the other side we see a reference to Praxiteles’ type of the Resting Faunwith arm set on hip. The lightness of movement and the delicacy of the upper bodies evoke Canova. However, a sort of overall “dignity” separates these figures from Canova as well as from the severity of Thorvaldsen. This feature constitutes Finelli’s characteristic ideal for he knew how to to interpret nobility and “grand” style even in works of “pleasing subject matter,” imbuing them with a “monumental character,” as a contemporary critic observed (Leoni, 1853, p 230).

In the Dancing Hours, “cosi lievi che giunte appena s’involano,” (so lightly do they touch that they seem to fly away) their gentle motion shuns every affectation thanks also to the philosophical ideals visible in the faces of the hours of the day, “that figure most joyful looking at her companion in the middle who is less ardent and lively, and who in turn touches the shoulder of the third figure whose face suggests quiet sadness,” the first symbolizing joy of the morning while the last figure, turning away, “evening’s melancholy” (Checchertelli 1854, p. 17).

In this second marble group the meditative nobility of the figures, together with their attributes embodies the same message as the Three Graces in which we understand the powerful civilizing force of poetry on humanity symbolized by the cithara but also, and just as importantly, by emblems of nature’s bounty:

“Observing the crowns of each Grace, one of flowers; another of wheat; the third of vines, persuades us that these Graces represent Nature, and that their smiles are directed to man and the earth which they bless with beautiful flowers in the spring, crops in summer, and grapes in fall (Checchertelli, 1854, p.29).

“E nell’osservarle una coronata di fiori l’altra di spiche la terza di pampini ti persuadi che le grazie sono esse della natura, le quali allietano del lor riso l’uomo e la terra; che guidano sovressa bella di fiori la primavera, di messe la state, di uve l’autunno.”(Ibidem, p.29).

Cited biographical references:

Campori 1873: Giuseppe Campori, Memorie biografiche degli scultori, architetti, pittori, ec. nativi di Carrara e di altri luoghi della provincia di Massa con cenni relativi agli artisti italiani ed esteri che in essa dimorarono ed operarono e un saggio bibliografico, Modena 1873.

Checchetelli 1854: Giuseppe Checchetelli, Carlo Finelli e le sue sculture, Cenni di G.C., Rome 1854.

Leoni 1853: Q.Leoni, Finelli, in “Album”, A.XX 1853, d.31, pp.229-232.

Milan 2001; Due dipinti di Pompeo Girolamo Batoni. Una scultura di Carlo Finelli, Galleria Carlo Orsi, Milan 2001.

Musetti 2001: Barbara Musetti, L’eredità della scultura classica nell’opera di Carlo Finelli (1782-1853), in “Studi di Storia dell’Arte”, 12 2001, pp.153-169.

Musetti 2002: Barbara Musetti, Carlo Finelli(1782-1853), Cinisello Balsamo 2002.

Rome 2003: Maestà di Roma da Napoleone all’Unità d’Italia. Universale ed Eterna. Capitale delle Arti, Exhibiiton catalogue (Rome, Scuderie del Quirinale, National Galley of Modern Art, 7thMarch – 29thJune 2003), project of Stefano Susinno, realized by Sandra Pinto with Liliana Barroero and Fernando Mazzocca, Milan 2003.