Detail

Detail

Detail

GIULIO ARISTIDE SARTORIO ROME, 1860 -1932

Further images

Provenance

Marga Sartorio collection, Rome; Private collection, Rome

Exhibitions

Sala del Lazio, Esposizione Internazionale del Sempione, Milano, 1906;

Crociera Regia Nave Italia 1924; G. A. Sartorio, Galleria del Levante, Milano, 1974;

Un fregio di Giulio Aristide Sartorio, Roma, Galleria dell’Emporio Floreale, 1974;

Giulio Aristide Sartorio. Figura e decorazione, Roma, Palazzo Montecitorio, Sala della Regina, 1989.

Literature

Esposizione di Milano 1906, Mostra Nazionale di Belle Arti, illustrated catalogue, Milan p. 39;

Dalla caduta di Roma imperiale alle conquiste ultime della scienza. Fregio decorativo di G. A. Sartorio, Danesi editore, Rome 1906, pp. 107 – 114;

Ugo Fleres, Ciò che Roma manda a Milano, in Milano e l’Esposizione Internazionale del Sempione 1906, Cronaca illustrata dell’esposizione compilata a cura di E. A. Marescotti e Ed. Ximenes, Fratelli Treves editori, Milan 1906, p. 130;

La decorazione della sala del Lazio, in ibidem, pp. 183-186;

Note di cronaca. La principessa Letizia visita l’Esposizione, in ibidem, p. 218;

I premiati all’Esposizione di Belle Arti, in ibidem, p. 352;

Raffaello Barbiera, Rivista delle Belle arti, in ibidem, p. 572;

Raffaello Barbiera, Le belle arti all’esposizione internazionale di Milano, in “L’illustrazione italiana” , Milan 28 April 1906, pp. 374 – 375;

Ugo Ojetti, L’arte all’esposizione di Milano. Note e impressioni, Fratelli Treves editori, Milan 1906, p. 46;

A. Milani, Note critiche sull’Esposizione Internazionale d’arte di Venezia. Le pitture di Sartorio e una pregiudiziale, in “Natura e Arte”, vol. XVI , Milan 15 June 1907, pp. 12,13,17;

M. de Benedetti, Giulio Aristide Sartorio Pittore, in “Nuova antologia”, a. XXXVII, vol. CXXVIII, Rome 16 April 1907, p. 593 – 600;

Luigi Serra, La campagna romana nelle tempere e nei pastelli di Giulio Aristide Sartorio, in “Emporium”, vol XVII, n. 160, Bergamo 1908, pp. 281 – 296;

Vittorio Pica, Il nuovo palazzo del parlamento italiano, in “L’illustrazione italiana, Milan 22 November 1908, pp. 490 – 494;

Luigi Serra, Il fregio di G. A. Sartorio per la nuova aula del Parlamento, in “Emporium”, Vol. XXIX, n. 169, Bergamo 1909, pp. 281 – 296;

I saloni d’onore della regia nave Italia: crociera nell’America latina, Stabilimento Grafico Reggiani, Milan 1924;

Mostra delle pitture di Giulio Aristide Sartorio nella regia Galleria Borghese, Rome 9 March-24 April 1933, Reale Accademia d’Italia, Rome1933, p. 54;

Pasqualina Spadini, Un fregio di Giulio Aristide Sartorio, Galleria dell’Emporio Floreale, Rome 1974;

Giulio Aristide Sartorio, 1860-1932, catalogue of the exhibition by Fortunato Bellonzi, Rome, Palazzo Carpegna 13 May-20 June, De Luca editore, Rome 1980;

Anna Maria Damigella, Il Fregio di Aristide Sartorio, in L’aula di Montecitorio, Basile, Sartorio, Calandra, Franco Maria Ricci editore, Milano 1986, p. 29;

Anna Maria Damigella, Sartorio e la pittura decorativa simbolica, in Giulio Aristide Sartorio. Figura e decorazione, exhibition curated by Bruno Mantura e Anna Maria Damigella, Rome Palazzo Montecitorio, sala della Regina 2 February – 11 March 1989, Franco Maria Ricci editore, Milan 1989, pp. 62 – 65;

Gioacchino Barbera, Anna Maria Damigella, I bozzetti di Sartorio per il duomo di Messina, Sellerio editore, Palermo 1989, p. 43;

Pasqualina Spadini, La Sirena e l’Arpiola, in Giulio Aristide Sartorio (1860 – 1932). Fra Simbolismo e Liberty, exhibition curated by Pasqualina Spadini e Lela Djokic with an introduction by Bruno Mantura, Galleria Campo de’ Fiori, Rome, aprile 1995, p. 29;

Teresa Sacchi Lodispoto, Sartorio cantore della Storia d’Italia, in Sartorio 1924. Crociera della regia nave Italia nell’America Latina, catalogue of the exibition curated by Bruno Mantura, Rome Istituto Latino Americano 9 December 1999 – 5 Februry 2000, De Luca editore, Rome 1999, pp 56 – 62;

Giulio Aristide Sartorio (1860-1932). Nuovi Contributi. Anni difficili, catalogue of the exhibition curated by Pasqualina Spadini e Lela Djokic, Nuova Galleria Campo de’ Fiori, Rome April 1999, p. 10;

Giulio Aristide Sartorio: il realismo plastico tra sentimento ed intelletto, Orvieto Palazzo Coelli, 8 May-18 July 2005, exhibition curated by Pier Andrea De Rosa and Paolo Emilio Trastulli, Arte cultura sviluppo, Orvieto 2005;

Maria Paola Maino, La vita avventurosa di un’opera, in Giulio Aristide Sartorio (1860 – 1932), catalogue of the exhibition curated by Renato Miracco, Rome Chiostro del Bramante 24 March -11 June 2006, Maschietto, Mandragora editore, Florence 2006, pp. 97 – 103;

Renato Miracco, Giulio Aristide Sartorio e “la veste vivente della divinità”, in Il fregio di Giulio Aristide Sartorio, ed. by Renato Miracco, Leonardo international editore, Milano 2007, p. 32;

Marina Miraglia, Sartorio, la fotografia e il fregio al parlamento, in ibidem, pp.79 – 90, in part. p. 90.

Giulio Aristide SARTORIO

(Rome 1860 –1932)

G.A. Sartorio in his studio in Fausta, 1910 c. Sartorio Archives

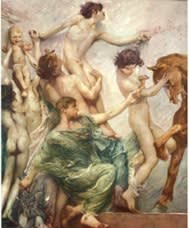

The panels presented in this publication mark the sensational rediscovery of parts of a large decorative frieze produced by Giulio Aristide Sartorio for the Esposizione Internazionale del Sempione of 1906 (1). The frieze was designed to decorate the Lazio Room, which hosted paintings by Sartorio himself along with others by Camillo Innocenti, Umberto Coromaldi, Arturo Noci, Vitalini, Enrico Lionne, Antonio Discovolo, Pietro Mengarini, Antonio Mancini, Norberto Pazzini and Paolo Ferretti. The frieze, painted in oil on canvas “en grisaille”, consisted in a set of panels in which the artist set out to illustrate “Italy’s driving energy in history, ferrying the classical ideal into the modern world” (2) and was devised “by spiritual association…like the bas-relief in Athena’s greatest temple.” (3) Reflecting the Esposizione’s own object of celebration, the dazzling modern achievement that was the Simplon tunnel, the topic addressed in the frieze was intended to be an apotheosis of man’s achievements. To translate this goal into images, the artist identified a series of key turning points in the history of mankind, the central one of which was the Renaissance inasmuch as it was considered the age of the rediscovery of humanist and civic values (4). Sartorio penned an introduction to the meaning of his symbolic figurations, deployed in a broad band along the upper part of the large room, in the exhibition catalogue. The series began with an illustration of the period stretching From the Fall of the Roman Empire and the Barbarian Invasions to the Renaissance, continued with the era stretching From the Great Discoveries, Through the Gloomy Ages, to the Living Revival of the Race and From the Fable of Pegasus to the New Achievements of the Liberal Arts, and ended with the period stretching From the Myth of Brute Forces Tamed to the Most Recent Achievements of Science (5). This herculean decorative scheme received ample coverage in the press and was reproduced in the leading periodicals of the time, Sartorio being described as the artist behind the “delightful decoration of the Lazio Room” (6) and being presented to Princess Letizia when she visited the Esposizione (7). On the same occasion he won a 5,000 lire prize for one of the paintings he was showing, the Monte Circeo, a large canvas depicting a scene set in the countryside near Rome (8). Ever since his return to Rome from Weimar (9) in the early years of the century, Sartorio had displayed a marked inclination to develop his art on the grand scale. Before tackling the frieze for the Simplon exhibition, he had already turned his hand to the wall decorations for the Lazio Room at the Venice Biennale of 1903 (10), which he painted with a Renaissance revival motif consisting in a group of nude putti carrying laurel wreath festoons; to the decorations for the Italian pavilion designed by Sommaruga for the St. Louis exhibition of 1904 (11); and to the decorative scheme for the Casa del Popolo in Rome in 1906, for which he produced a partial revisitation of his 1903 frieze with nude putti 1903 (12). The practice of revisiting his earlier work, either in whole or in part, is recorded on a number of occasions in the course of Sartorio’s career and he resorted to it again with this frieze, reworking it in 1923 for the cruise of the Royal Yacht “Italia” when, in his capacity as Commissioner for the Arts, he took upon himself the task of familiarising the world with Italian art by conducting an eight-month tour of Latin America (13). The fact that he felt it appropriate on such a prestigious occasion to use a work created in 1906, in other words almost twenty years earlier, provides us with confirmation of the fact that it was considered to be in the forefront of style.

By comparison with his earlier decorative schemes, From the Fall of the Roman Empire to the Most Recent Achievements of Science had withstood the test of time inasmuch as it marked a turning point in the artist’s career because it had compelled him to tackle a far more complex and many-sided theme than those that he had addressed hitherto.

Anna Maria Damigella has perceptively pointed out that the “frieze painted in monochrome for the Lazio Room… is the first work in which Sartorio proposes a potential pathway for modern decoration in a programmatic sense” (14). The painter arranged his figures, his men, women and animals, in sculptural poses the length of a broad decorative band in a manner that heralded his future decorative work, paving the way both for the style of The Poem of Human Life (four canvases, each seven metres long by five high, with allegories of Light, Darkness, Love and Death painted the following year for the Venice Biennale of 1907) and for the development of the symbolic figurations and decorative motifs to which he was to return a few years later in his greatest work of all, a mammoth frieze for Montecitorio (1908–12) (15).

Ugo Ojetti discusses From the Fall of the Roman Empire to the Most Recent Achievements of Science in a lengthy essay on the artists showing in the Lazio Room, his choice of words suggesting that he appreciated Sartorio more for his technical skill than for the way in which he developed his complex significations. Ojetti writes: “Giulio Aristide Sartorio has crowned this fine room, named after him, with a frieze painted ‘en grisaille’ which, apart from the apocalyptic symbols that the artist explains with a wealth of initial capitals in two pages of the catalogue (Sartorio is also a novelist), is splendidly decorative in its effect thanks to a skilful distribution of high and low relief…” (16).

Despite the fact that the significations developed by the artist were occasionally considered to be excessively obscure, the frieze continued to attract attention for several years after the Simplon exhibition had ended. Indeed Luigi Serra, writing in 1908, described it as one of Sartorio’s most successful decorative undertakings: “… the current exhibition represents the expressive pinnacle of Sartorio’s sculptural activity, not because he lacks either the strength or the will further to expand and perfect this marvellously vibrant aspect of his talent, but because of the attraction that he feels towards a more complex manifestation of art. Sartorio is drawn today to large-scale decorative compositions, two magnificent instances of which are his friezes in Milan (1906) and in Venice (1907), which will serve him as preparatory works for the frieze in the Chamber of Deputies. With these works – which mark a new and stupendous moment in the troubled development of contemporary Italian art on account both of the breadth and depth of their conception and of the restrained skill displayed in their execution – Sartorio has earned his place at the head of the painting movement in Italy. And given that he is in the prime of his life, we may reasonably expect him to produce many more solemnly successful works and to spearhead a new renaissance in our country’s art.” (17). Serra’s words set the work in a dignified position within the artist’s career, and indeed it was still being discussed in 1933 in the catalogue of an exhibition held in the Galleria Borghese (18), where mention is made of the “Pre-Raphaelitism” which Sartorio is said to have displayed in the decorations that he produced for Gabriele d’Annunzio when, “with elegant imagination, accomplished hand and singular deftness” (19), he painted four panels in “the Byzantine style” for Isaotta Guttadauro. An interest which prompted him to travel to England in 1893 precisely to study the Pre-Raphaelites, as well as to see the magnificent Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon in the British Museum with his own eyes.

For the decorative frieze in the Lazio Room, however, we need to look to Sartorio’s formative years rather than to his interest in the Anglo-Saxon world. Born in Rome into a family of artists, he undoubtedly had an opportunity to admire Raphael’s Stanze in the Vatican – and more especially the part below The Parnassus (1510–11) painted “en grisaille“ in the Stanza della Segnatura – and thus to take a serious interest in the master’s rich and fervent style. His interest in the Stanze is in fact borne out by La Favola di Sansonetto Santapupa, a novel penned by Sartorio and published between 1926 and 1929, in which he recounts the story of a sculptor’s son. Rich in autobiographical details, the young artist Sansonetto/Sartorio descibes how deeply unsettling and astounding he found the decorations in the Vatican Stanze to be: “….Sansonetto emerged from the Vatican in a daze; the spectacle of the Renaissance seemed to him to be the spectacle of life and he considered that he, a mere boy, had the right to portray himself alongside the Renaissance in exactly the same manner as Perugino, Raphael and Bramante had portrayed themselves among the figures in Attica….” (20).

It was from here, in the very heart of Rome, that the artist drew the inclination to work on large-scale decorative schemes that was to allow him to become a painter of international renown and, while his desire to create a precious and exclusive object in the “service” of its surroundings may prompt us on the one hand to assign his work to the variegated context of English Arts and Crafts with which he was unquestionably very familiar, at the same time it also makes it easier to explain the painter’s interest in the style of the Pre-Raphaelites and, in particular, of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose fervent admirer he was and of whom had written on more than one occasion (21) to the point where he sought his inspiration in Rossetti’s art, for example for the features of his young girls so akin, in particular, to those of the announcing Madonna (22).

Notes

- In recounting the history of these works of art over more than a hundred years, we are duty-bound to acknowledge both the crucial contribution of Maria Paola Maino who first rediscovered them in 1974, and the pioneering research conducted by Pasqualina Sadini to whose memory I would like to dedicate these pages.

- Dalla caduta di Roma imperiale alle conquiste ultime della scienza. Fregio decorativo di G. A. Sartorio, Danesi editore, Rome 1906, p. 107

- Ibid.

- Anna Maria Damigella, Sartorio e la pittura decorativa simbolica, in Giulio Aristide Sartorio. Figura e decorazione, exhibition curated by Bruno Mantura and Anna Maria Damigella, Rome, Palazzo Montecitorio, Sala della Regina 2 February–11 March 1989, Franco Maria Ricci editore, Milan 1989, p. 63

- See: Giulio Aristide Sartorio, Descrizione del Fregio Decorativo per la Sala del lazio, in the present catalogue pp. 30-31

- Raffaello Barbiera, Rivista delle Belle arti, in Milano e l’esposizione Internazionale del Sempione 1906, illustrated report on the Exhibition compiled by E.A. Marescotti and published by Ximenes, Milan, Fratelli Treves editori, 1906, 572

- News item. Princess Letizia visits the Exhibition, in ibid., p. 218

- The Fine Arts Exhibition’s Award-Winners, in ibid., p. 352

- Sartorio was in Weimar from 1896 to 1899, teaching at the Grand Duke of Saxony’s Fine Art School (see Pasqualina Spadini, La Sirena e l’arpiola, in Giulio Aristide Sartorio, catalogue of the exhibition curated by Pasqualina Spadini and Lela Djokic, Nuova Galleria Campo de’Fiori, Rome April 1999, p. 15)

- “… The room, which is one of the largest and, I believe, also one of the highest in the Venice exhibition, has all around its upper part, set between two thin golden mouldings, a large chiaroscuro frieze depicting a group of naked putti supporting a laurel wreath festoon. Devised by Sartorio and produced by him with the valuable assistance of another six Roman artists – Carlandi, Coromaldi, Innocenti, Nardi, Noci and Poma – it is a work of exquisite pictorial elegance...” (see Vittorio Pica, L’arte mondiale alla V Esposizione, Istituto italiano d’Arti Grafiche, Bergamo 1903, pp. 32-33)

- According to a report by M. de Benedetti in Giulio Aristide Sartorio Pittore, in “Nuova antologia” a. XXXVII vol. CXXVIII, Rome 16 April 1907, p. 593 – 60, repeated in P. Spadini, Un fregio di Giulio Aristide Sartorio, Galleria dell’Emporio Floreale, Rome 1974, p. 7; yet Sartorio’s name does not appear in the exhibition’s substantial catalogue (see Official Catalogue of Exhibitors, Universal Exposition, St. Louis, U.S.A., 1904)

- Anna Maria Damigella, Sartorio e la pittura decorativa … op. cit. (1989), pp. 59 – 62

- Maria Paola Maino, La vita avventurosa di un’opera, in Giulio Aristide Sartorio (1860 – 1932), catalogue of the exhibition curated by Renato Miracco, Rome, Chiostro del Bramante 24 March–11 June 2006, Maschietto, Mandragora editore, Florence 2006, pp. 97-103;

- Anna Maria Damigella, Il Fregio di Aristide Sartorio, in L’aula di Montecitorio, Basile, Sartorio, Calandra, Franco Maria Ricci editore, Milan 1986, p. 29

- Revived in their turn in the cartoons for the mosaic decoration of Messina Cathedral, produced posthumously from 1935 to 1940 (see Gioacchino Barbera, Anna Maria Damigella, I bozzetti di Sartorio per il duomo di Messina, Sellerio editore, Palermo 1989)

- Ugo Ojetti, L’arte all’esposizione di Milano. Note e impressioni, Fratelli Treves editori, Milan 1906, p. 46

- Luigi Serra, La campagna romana nelle tempere e nei pastelli di Giulio Aristide Sartorio, in “Emporium”, vol XVII, n. 160, Bergamo 1908, pp. 281–296

- Exhibition of paintings by Giulio Aristide Sartorio in the Regia Galleria Borghese, Rome 9 March–24 April 1933, Reale Accademia d’Italia, Rome 1933, p. 54

- Letter from D’Annunzio to Errico dated 1889, cited in Anna Maria Damigella, Sartorio e la pittura decorativa… op. cit. (1989), p. 44

- La favola di Sansonetto Santapupa, in “La Rassegna Nazionale”, 1926-29 (now in: Giulio Aristide Sartorio: il realismo plastico fra sentimento ed intelletto, Orvieto, Palazzo Coelli, 8 May–18 July 2005, curated by PierAndrea De Rosa and Paolo Emilio Trastulli, pp. 127-198

- Aristide Sartorio, Nota su D. G. Rossetti pittore, in “Il Convito”, Libro II, February 1895, pp. 121-150 and Nota su D. G. Rossetti pittore, II parte, in “Il Convito”, Libro III, April 1895, pp. 261-286

- see Giulio Aristide Sartorio 1860-1932, exhibition curated by Fortunato Bellonzi, Rome, Palazzo Carpegna 13 May–20 June 1980 De Luca, Rome 1980, p.25

The signature and date on the upper right-hand edge of the panel depicting The Advent of Art and Culture – “GA Sartorio, Roma MCMXXIII” – tell us that, of the three panels rediscovered, this is the one that the artist reworked most extensively in 1923 when adapting them for the Royal Yacht “Italia”. The central portion with the inscription and the two young girls above it appears to have been almost completely repainted (apart from the back of the young man seen behind the girl on the left), while the two wings are a product of the merging of four different portions from four different canvases depicting moments unrelated in the initial narrative. Also, virtually all of the figures and backgrounds have been partly retouched with a palette that is visibly lighter than the original, with the unmistakable milky white and the eager green brushstrokes that help to impart a greater sense of dynamism to the narrative.

By comparison with the two wings, therefore, the central part is far closer to the Montecitorio frieze in both stylistic and compositional terms, a contention borne out by the wind-ruffled drapery of the two girls’ tunics, so similar to the drapery depicted in paintings now owned by the Fondazione Cariplo and also dated 1923.

Sagra (Festival), 1908–23, tempera on canvas, 180,5 x 398,5 cm., Fondazione Cariplo, Milan

According to Sartorio’s description of the decorative frieze penned in 1906, in the two wings we see “the athletes who people the composition at regular intervals and symbolise the race“. The athletes on the left come from “Reconquering the Liberal Arts“, while those on the far right come from the panel entitled “From the Barbarian Invasions to the Renaissance“.

The groups of figures in the middle partake of the joyous mood: “The artists revive Venus, the scholars decipher inscriptions and the new knighthood adores the tenth Muse. A choir sings praises, and while secular music educates the young to rhythm, shipwrights build the ship that will spread the Renaissance throughout the world“.

The left-hand band refers to part of “…The new Latin signification (which) begins with the exercise of the arts, and from the revival of the ancient world the people acquire an awareness of self. The artists revive Venus, the scholars decipher inscriptions…”. The figures include a man kneeling and offering a statuette, clearly heralding the part of the Montecitorio frieze in which Sartorio was to portray himself kneeling to symbolise the offer of beauty.

Giulio Aristide Sartorio, Frieze for Montecitorio, Rome, (detail), 1912

The two groups on the left and right, though originally from different panels, may thus be assigned to the multi-faceted description of the advent of the Renaissance, an era which Sartorio considered to mark the pinnacle of Italy’s achievement in the arts and, possibly with the Advent of Art and Culture, he may also have been alluding to the advent of a new renaissance ideally prompted by the tour of Latin The two groups on the left and right, though originally from different panels, may thus be assigned to the multi-faceted description of the advent of the Renaissance, an era which Sartorio considered to mark the pinnacle of Italy’s achievement in the arts and, possibly with the Advent of Art and Culture, he may also have been alluding to the advent of a new renaissance ideally prompted by the tour of Latin America – the journey on which he was preparing to set out in the Royal Yacht “Italia” in order to promote Italian art in the wider world.

ROOM IV - LAZIO GROUP

depicted by the Painter GIULIO ARISTIDE SARTORIO

DESCRIPTION OF THE DECORATIVE FRIEZE

The procession illustrates Italy’s driving energy in history, ferrying the classical ideal into the modern world. By spiritual association, the action entered into to free mankind from mental slavery, from northern European mysticism, is designed like the bas-relief in Athena’s greatest temple. The first wall, from right to left, includes the legends: From the fall of the Roman Empire and the barbarian invasions to the Renaissance. The narrative begins with the moment which, for Italy, inevitably summed up Tradition in its entirety: a barbarian topples the symbols of the Caesars, while the people tear each other apart in wars of religion and the invasion advances like a horse unbridled and goaded on by a destructive fury. The building collapses and two athletes hold it up. All the athletes who people the composition at regular intervals symbolise the race. This is the introduction. The new Latin signification begins with the exercise of the arts, and from the revival of the ancient world the people acquire an awareness of self. The artists revive Venus, the scholars decipher inscriptions and the new knighthood adores the tenth Muse. A choir sings praises, and while secular music educates the young to rhythm, shipwrights build the ship that will spread the Renaissance throughout the world. The second wall, from left to right, includes the legends: From the great discoveries through the gloomy ages, to the living revival of the race. The antecedent shows a parallel for the Invasion, with the picture of the Domination. At the beginning we see the mystic image of the Holy Roman Empire, and at the end the final evocation of the spectre that followed on from the Revolution. Between these centuries in Room IV, domination: Italian energy conquers the surface of the globe and universal notions. Boatmen offer Minerva the sphere of the globe, and astronomers and scientists, in adoration before the great Pantheistic Mother, enumerate the stars and the planets, causing Electricity to burst forth from the earth. After the indigite athletes, we see the start of the restoration of the race’s fortune amid rural activities such as cultivating the vine, the olive tree, oats, corn and wheat. Among the workers are two symbols: the statue of Saturn, an ancient god, and “the new and holy Venus of Italy”, a popular glorification of the maternal idyll. The short walls host the Apotheoses for the present achievements of the arts and sciences, including the legends: From the fable of Pegasus to the new achievements of the liberal arts. The prelude depicts the mystic birth of Pegasus: two genies carry the Aegis and the Gorgon. Thereafter, the Italian soul arises anew out of the Dionysiac sarcophagus, and the choir braces itself for the new march forward. Under an arch, the figure of Art, shown in the guise of Athena, nourishes with energy the lions that are close to her heart, and from the foundations, Symony laboriously raises the monstrous emblem of the amphibians. This is followed by the action, the players move, a boy lifts a lyre to the winds, and two Victories hold open the book of Inventions. A genie raises the last sculptural figuration to the height of the book. The fourth wall includes the legends: From the myth of brute forces tamed, to the most recent achievements of science, a prelude to the Apotheosis, a Victory keeping the lions in subjugation. Beyond the caryatids, nymphs pour out the strength of the waters, and Invention transmits Electricity as the life of a new being. Nikè Àptera announces the most recent achievement spawned by Italy’s energy and spirit: men communicating with each other across the arc of the sky, over mountains and across the ocean. This figure concludes the design, which has unfurled in a seamless space, so dear to Mediterranean Civilisation.

-

GIULIO ARISTIDE SARTORIOFrom the Myth of Brute Forces Tamed to the Most Recent Achievements of Science, 1906

GIULIO ARISTIDE SARTORIOFrom the Myth of Brute Forces Tamed to the Most Recent Achievements of Science, 1906 -

GIULIO ARISTIDE SARTORIOFrom the Great Discoveries, Through the Gloomy Ages, to the Living Revival of the Race, 1906

GIULIO ARISTIDE SARTORIOFrom the Great Discoveries, Through the Gloomy Ages, to the Living Revival of the Race, 1906 -

GIULIO ARISTIDE SARTORIOA morning at the seaside, 1927

GIULIO ARISTIDE SARTORIOA morning at the seaside, 1927 -

VITALIANO MARCHINIArdito (Male portrait), 1919

VITALIANO MARCHINIArdito (Male portrait), 1919