-

Artworks

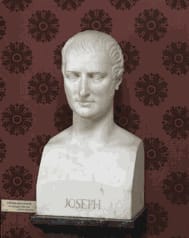

LORENZO BARTOLINI SAVIGNANO DI PRATO, 1777-FLORENCE, 1850

Herm, Portrait of Joseph Bonaparte, 1808Carrara marbleh 57 cmInscribed on the base:"JOSEPH"

SOLD

PALAIS FESCH. MUSÉE DES BEAUX ARTS, AJACCIO

Provenance

Elisa Bonaparte (1777–1820) Principessa di Lucca e Piombino, Contessa di Compignano, Duchessa di Massa and Principessa di Carrara, Granduchessa di Toscana (from 1809 to 1814);

Joseph Bonaparte (1768–1844) Re di Napoli (1806-1808) and then Re di Spagna (1808 - 1813);

Zenaide Letizia Bonaparte (1801–54) Principessa di Canino e Musignano;

Giulia Bonaparte (1830–1900), Marchesa di Roccagiovine;

Marchese Alberto del Gallo di Raccagiovine (1854 - 1947);

Marchesa Matilde del Gallo di Roccagiovine (1888-1977);

Oliviero Bucci Casari, Conte degli Atti di Sassoferrato;

Nobildonna Bucci Casari, Contessa degli Atti di Sassoferrato.This portrait of Joseph Bonaparte in the form of a herm is an autograph work by Lorenzo Bartolini, an attribution borne out not only by the sculpture's lofty quality and the unmistakable characteristics of Bartolini's style but also – indeed primarily – by its prestigious provenance, for the portrait originally belonged to Elisa Baciocchi Bonaparte.

The absence of a signature, which in no way invalidates the attribution, can easily be explained if we carefully review Bartolini's years in Carrara during the Napoleonic era; and this, even though only a handful of works and documents remain from that time on account of the destruction visited on the Carrara workshop of the sculptor (who never made any secret of his veneration for Napoleon) during the anti-French riots in Carrara in late 1813, duly reported by Tinti in his crucial monograph on Bartolini published in 1936[1].

On 30 October 1807, taking up a suggestion made by the powerful Dominique Vivant-Denon, the director of the Musée Napoléon, Napoleon personally appointed Bartolini to the post of professor of sculpture at the school run by the Accademia di Belle Arti in Carrara, where he was to take the place of the sculptor Angelo Pizzi. Bartolini, however, was less than enthusiastic about the appointment. He had no intention of leaving Paris and of thus ending his stormy love affair with Mademoiselle Scio. In the end, however, he reluctantly moved to Carrara in January 1808. His teaching post also included the directorship of the sculpture workshops which were busy turning out ornamental works, copies of Classical sculpture and portraits of Napoleon and his extended family with funding from the Banca Elisiana.

The production of busts, based on faithful copies or original revisitations of models by such celebrated sculptors as Canova, Chinard, Chaudet and Bosio, were primarily intended for French patrons. The Banca Elisiana established by Baciocchi in May 1807 and managed by Hector Sonolet, the director general of the Accademia's museums and administrative director of the marble trade, was to all intents and purposes a bank for helping and issuing loans to artists and artisans working in the field of sculpture in Carrara.

Fig. 1:

F. Delaistre, Joseph Bonaparte, King of Naples and then King of Spain, 1808;

Versailles, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon (detail).

The bank's purpose was to boost the local production of finished marble sculpture by seeking to create employment locally and, in introducing stiff customs tariffs, to discourage the export of unhewn blocks for carving in other areas of Italy and Europe. The concern was capitalised to the tune of 300,000 francs and employed hundreds of sculptors and artisans in the numerous sculpture workshops which it either owned or merely managed[2].

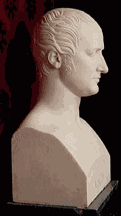

Fig. 2:

Lorenzo Bartolini, Herm, portrait of Jospeh Bonaparte, 1808-1809; Versailles, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. Inscription “Bartolini dir.”. (side view of fig.2)

In addition to his role as teacher at the Accademia and to the work commissioned from him directly, Bartolini was also tasked with overseeing the sculpture commissioned from the workshops through the bank. This, because over the many years he had spent in the company of his lifelong friend Ingres in David's workshop in Paris (1799–1808), Bartolini had acquired a certain renown and built up a reputation for himself as an outstandingly talented sculptor.

The task of copying casts of portraits despatched to Carrara was entrusted directly to the workshop sculptors under Bartolini's direction – indeed many of the busts bear the inscription "Bartolini dir." – and they were reproduced using a pointing machine. The Banca Elisiana had hired the most talented Carrara sculptors to carve the works, a fact which, in the absence of any signature, makes it well nigh impossible to attribute surviving busts – many of them of remarkable quality – with any certainty. The artists hired included sculptors, for example, of the calibre of Bartolomeo Franzoni, Giovanni Andrea Pelliccia, Paolo Triscornia and Pietro Marchetti.

Fig. 3:

Lorenzo Bartolini, Herm portrait of Jospeh Bonaparte, 1808-1809; Versailles, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. Inscription: “Bartolini dir.” (veduta laterale dell’erma a fig. 2).

Rather than revisiting the portraits with a touch of originality, it was the practice to make a plaster model and sometimes even a prototype in marble. We may assume that the marble prototypes, made by other artists as well as Bartolini (Pietro Marchetti, for instance, was a sculptor whose work was much appreciated by Elisa Baciocchi and by Sonolet), were intended for Elisa, as with the bust under discussion here, and possibly on occasion also for other members of the imperial family. These prototypes often then served as the basis for copies, frequently unsigned and devoid of all inscription, or occasionally bearing the legend "Bartolini dir." If the copy was commissioned from a talented sculptor of renown, on the other hand, the artist would very often sign it.

Fig. 4:

P. Triscornia, from L. Bartolini, Herm, portrait of Jospeh Bonaparte, 1808-1809; Versailles, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon.

And finally, it is worth pointing out that marble prototypes were also frequently unsigned, as is the case with this herm of Joseph.

Tinti and Hubert, both extremely reliable sources, attribute the portrait of Joseph Bonaparte to Bartolini who in all likelihood carved it in 1808, revisiting a plaster cast from Paris in a highly original manner. The cast may have been from the face on a full-figure statue of Joseph Bonaparte completed by François Delaistre in 1808[3] (fig. 1), although Bartolini's model differs from it considerably. Bartolini's portrait is the result of a radical formal simplification (displaying an extremely modern approach in this), of a strongly idealised naturalism and of a linear stylisation of a conceptual nature which are typical features of Bartolini's art at that time and which are mirrored in the primitivism being developed in the field of painting by his friend Ingres in those same years.

Unlike other portraits of members of Napoleon's family, very few likenesses of Joseph have come down to us. The first is a herm now in Versailles, bearing the legend "Bartolini dir." on its left-hand side (figs. 2-3). The portrait, which has the typically static air of a copy, is listed in an inventory of the sculptor Cincinnato Baruzzi drafted in Bologna on 30 May 1854 mentioned by Jean-Pierre Samoyault in an essay on Elisa's collections written in 1983[4]. The bust is also mentioned by Tinti in 1936 and by Hubert in 1964[5]. Another portrait, again in the form of a herm, is now in Malmaison and bears the signature of Paolo Triscornia (fig. 4). Despite its acceptable quality, Triscornia's herm is a far cry from the extraordinarily lofty quality and sophistication of the herm under discussion in this paper. Hubert also reproduces a bust, again in Versailles (fig. 5), and mentions further busts, one at the Museés d'Arenenberg and another to be found (at the time, in 1964) in the Bourdier Collection, but very much smaller (h 35 cm) than the others and of inferior quality[6]. It has not, however, been possible to track down any further references to the latter two busts.

Fig. 5:

L. Bartolini, Herm, portrait of Jospeh Bonaparte, 1808-1809; Versailles, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon.

The bust under discussion here, of considerably higher quality than the handful of other known examples and typical of Lorenzo Bartolini's work in design, style and technique, may thus – also in view of the fact that we know it to have belonged to Elisa Baciocchi – be considered to be the marble prototype which Bartolini carved in 1808 and on which the other existing copies were then based.

- Francesco Leone

[1] M. Tinti, Lorenzo Bartolini, 2 vols., Rome 1936 : I, p. 63.

Still of crucial importance for Bartolini's activities in Carrara are: P. Marmottan, Les Arts en Toscane sous Napoléon. La princesse Elise, Pisa 1901; G. Hubert, La sculpture dans l'Italie napoléonienne, Paris 1964. Now see also E. Spalletti, Sull'attività di Bartolini al tempo di Carrara e su alcune commissioni per la Reggia Imperiale di Pitti, in Lorenzo Bartolini. Atti delle giornate di studio (Florence, 17–19 February 2013, Gallerie dell'Accademia – Gabinetto G.P. Vieusseux), ed. S. Bietoletti, A. Caputo, F. Falletti, Pistoia 2014, pp. 39-47.

[2] For the Banca Elisiana's activity see R. Carozzi, La Scuola di Carrara tra Canova e Bartolini, in Scultura, marmo, lavoro: maestri, giovani artisti, ricerche tecniche, exhibition catalogue (Carrara, Massa, Pietrasanta, June – August 1981), ed. M. De Micheli, Milan 1981, pp. 219-231; Id., Artisti e artigiani sotto il segno dell'Impero a Carrara, in Il Principato napoleonico dei Baciocchi (1805-1814). Riforma dello Stato e società, Conference Proceedings (Lucca, 10 – 12 May 1984), ed. V. Tirelli, Luca 1986, pp. 437-450; L. Passeggia, Carrara e la Francia, in Arte, gusto e cultura materiale, in Italia, Europa e Stati Uniti tra XVIII e XIX secolo, ed. L. Passeggia, Milan 2005, pp. 232 – 301; B. Musetti, Lorenzo Bartolini e la "Banca Elisiana". Ovvero la fabbrica della scultura, in Lorenzo Bartolini scultore del bello naturale, exhibition catalogue (Florence, Galleria dell'Accademia, 31 May – 6 November 2011), ed. F. Falletti, S. Bietoletti, A. Caputo, Florence 2011,pp. 147-151.

[3] See M. Tinti, op. cit., II, p. 27; G. Hubert, op. cit., p. 352.

[4] Samoyault, Tableaux, sculptures at meubles provenant d'Elisa Bonaparte, in Bullettin de la Societe de l'Histoire de l'Art français, 1983

[5] M. Tinti, op. cit., II, p. 27; G. Hubert, op. cit., p. 352, fig. 172.

[6] G. Hubert, op. cit., p. 352, note 2; figs. 171-172. Triscornia's Malmaison herm, reproduced by Hubert (fig. 171), was shown in 1928 at the De Napoléon Ier à Napoléon III: souvenirs de la famille impériale conservés par l'Impératrice Eugénie dans sa résidence de Farnborough et provenant de sa succession exhibition at the Musée National de Malmaison, Paris 1928, cat. 10; the same exhibition also hosted the scaled-down copy mentioned by Hubert in the Bourdier Collection: cat. 22.

Join the mailing list

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive all the news about exhibitions, fairs and new acquisitions!