Giovanni BONAZZA Venice 1654-Padua 1736

Further images

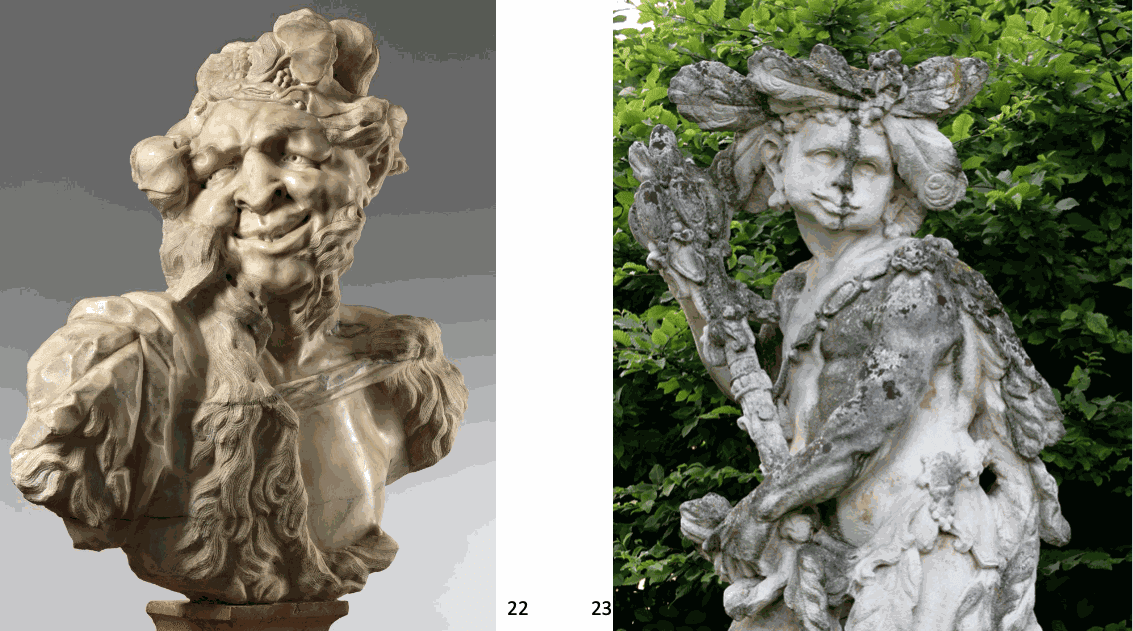

The previously unseen Bust of Bacchus presented here is a work which immediately betrays the hand of the Venetian Giovanni Bonazza, for its profoundly anti-classical language, and those examples of poetic licence that are its primary characteristic feature. Although a great deal of work remains to be done, today we can confidently affirm that we know Venetian sculpture of the Baroque age infinitely better than fifty years ago, and many other busts are therefore known that can be referred to Bonazza himself or to his contemporaries, which allow us to place this tour de force of the chisel within a contextual frame. And yet it is still a pinnacle of virtuosity and expressiveness that is characterized equally by its exceptional size and because it is not truly a bust in the round.

Bonazza may have been the one who took the language of Giusto Le Court and the Venetian Baroque in general to the extreme, to arguably become its most typical representative for us today, in his desire to be daring without ever being afraid of overdoing it. In this respect, this Bacchus may be his most paradigmatic work, a superior and eloquent example of what Rudolf Wittkower, as early as 1958, referred to as the “bombastic, painterly, and refreshingly unprincipled Late Baroque” of Venice.[1] A style which today’s Americans might call ‘larger than life’, a definition that perfectly fits this outsized Bacchus.

Within Bonazza’s corpus, it is no easy matter to date the large part of the production of marbles intended for a private clientèle, a category which this Bacchus belongs to. On this aspect of the sculptor’s activity, in addition to that of his contemporaries, we still know very little compared to what we know about their public activity thanks to signatures, archival documents, and literary sources. This Bacchus, which has now returned to the attention of scholars, is undoubtedly the apex of this part of Bonazza’s production. It is worth noting from the outset that only very few of the known works executed for private patrons and attributable to Giovanni including reliefs and statuettes of both secular and sacred subjects, appear to be signed (a series of reliefs in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore are signed,[2] as is the medallion with the portrait of Clara Buzzaccarini from a private collection, inscribed on the back BONAZZA 1714).[3]

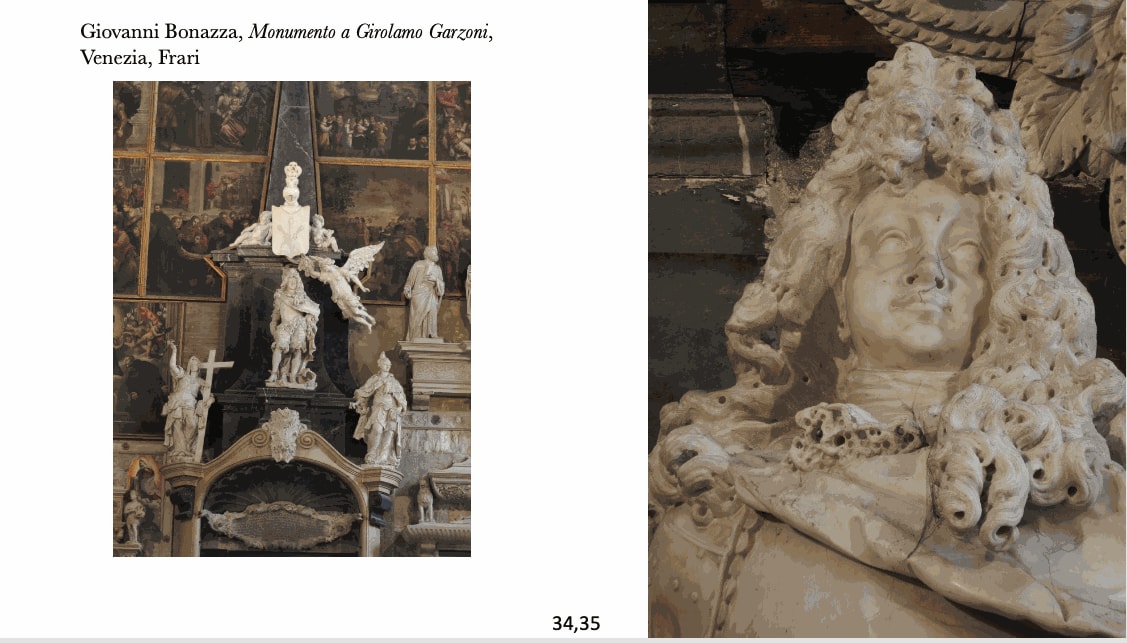

Starting from the Venetian consecration marked by the marbles of the Funeral Monument of Bertuccio Valier in the Basilica of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice (1704-1707), Bonazza signed his public works with a certain frequency, very rarely extending that habit, one might say, also to those for private clients.[4] Nor, on the other hand, are any signed garden statues of Bonazza known (other than, of course, the completely exceptional pieces sent to St Petersburg). Indeed, the busts made for Tsar Peter I the Great, now kept in the Summer Garden, are all signed “IO: N BONAZZA”.[5]

Among the few other documented busts of this prolific sculptor are those almost contemporary ones in the Donà Grimani Sorlini Castle overlooking Montegalda. In contrast, nothing is known about the commissioning, dating, and initial location of the four busts of Attila, Berengar, Alaric and Totila in Palazzo Roncali in Rovigo, attributed to Bonazza on the basis of a comparison with the reliefs in the Civic Museum of Padua which will be discussed shortly.[6]

Despite the major advances in our knowledge, no news has resurfaced to date about Bonazza’s activity in the field of portrait busts, a genre which, in the Serenissima of the 17th century, seems to have been introduced by Le Court,[7] Bonazza’s first teacher. If, as was only natural, the portrait bust spread first of all within the birthplace of Baroque sculpture, that is, in the Rome of the thirties, that of the mythological or allegorical subject enjoyed exceptional fortune in Venetian collecting at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, possibly even surpassing that which the same type had known or was experiencing in other contexts, such as in Rome itself.

Reproduced for the first time by Simone Guerriero, on the basis of a brilliant insight of Camillo Semenzato, are two Paduan busts by Bonazza, preserved in the Botanical Garden, depicting Flora and Zephyr (or perhaps Vertumnus),[8] marbles which also due to their remarkable state of conservation are imagined to have initially been made for an interior, and which are, among the sculptor’s works, those that hint most at the influence of Filippo Parodi. Auctioned at Sotheby’s in London on 3 December 2019 (no. 84), was a piece that is analogous in terms of workmanship and type, another Bust of Bacchus whose joyful and almost light-hearted character immediately betrays Bonazza’s hand. Finally, a pair of busts depicting Bacchus and Ariadne, also in a private collection, in which Ariadne’s eyes are sculpted with that love for soft curved lines that was the sculptor’s unmistakable hallmark, are unquestionably by Bonazza.[9]

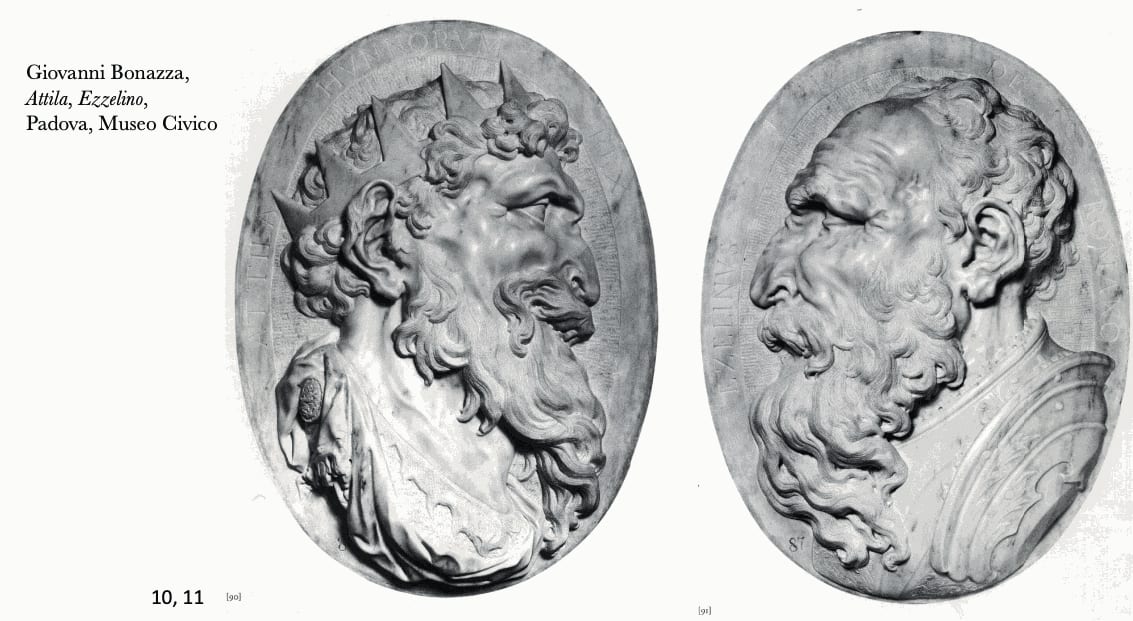

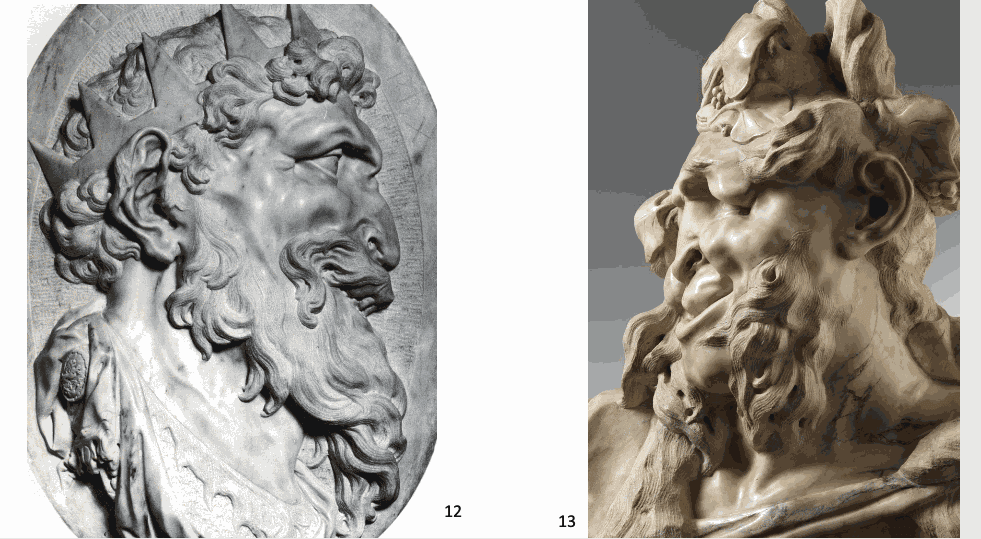

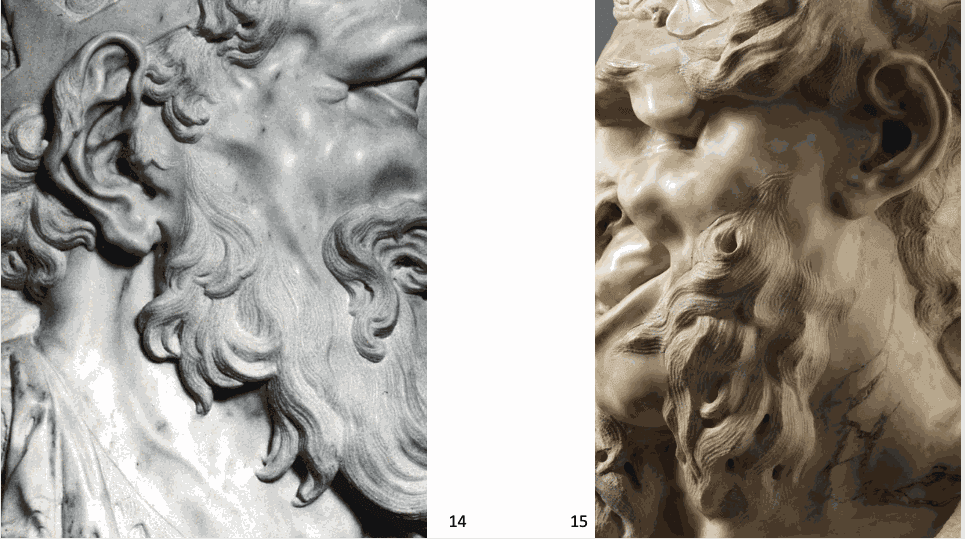

Bonazza’s corpus of gallery marbles is being reconstructed not so much thanks to a comparison with the less sensational documented or signed pieces at Montegalda, Padua and St. Petersburg, but thanks to the reliefs which until today could be considered the artist’s masterpieces in the field of sculpture for a private patron, that is, until the discovery of this Bacchus. We are referring here to the by-now famous and monumental relief medallions depicting, in profile, Ezzelino da Romano and Attila (68 x 50 cm), today in the Civic Museums of Padua (Figg. 10-12, 14, 16, 18) and coming from the Convent of San Giovanni di Verdara, suppressed in 1783.[10]

These magnificent marbles share the same provenance with many other reliefs of illustrious men from Medieval and Renaissance history, again kept in the Civic Museums of Padua, but originally commissioned by Abbot Ascanio Varese for the library of the Convent of San Giovanni di Verdara.[11]. It was precisely the Attila and Ezzelino, in which Bonazza overdid things to bring out their animalistic aggressiveness, their role as tyrants, which offer the highest examples of that vein which, with a changed form, emanates from the Bacchus in question.[12] The god of wine is depicted in the act of smiling, facing right, his head crowned with bunches of grapes and his shoulders barely covered by a pelt, which falls down his chest. The twisting of the face, heavily pronounced, supports the hypothesis that this bust was originally coupled with another (an Ariadne? a Ceres?), but obviously this is merely a suggestion (remembering, in any case, that a pair of busts by Bonazza depicting Bacchus and Ariadne does remain). The pupils of the eyes are deeply engraved, with a simple hole: this is almost unique in Bonazza’s corpus (but we must also remember the barbarian kings of Palazzo Roncali in Rovigo that feature a similar solution). The bust actually has very little pronounced relief, especially in the chest, and standing in front of it one immediately has the impression that it was designed to be inserted in a niche and seen from below. On the contrary, and this is the characteristic which makes it an absolutely exceptional, peerless piece, if we take a close look at the work, also in profile and from behind, we realize that it is not even a real bust, since the marble has been sculpted in such a way as to suggest the impression of being in front of a three-dimensional piece, when instead this Bacchus is something indefinable, a sculpture midway between a relief and a work in the round. The pedestal on which it is presented today, in all likelihood, must have been supplied at a later date, given that it is too large compared to the horizontal section of the bust, which originally, as just mentioned, was presumably placed inside a niche, albeit shallow, since it should have allowed a lateral view of the sculpture, at least in part.

It is unlikely that this Bacchus was placed on a free-standing base in space, such as a column or a stool, or even a console, because in that case it would have been evident that the entire rear of the marble, starting immediately behind the right ear or the grape vine on the left, was never carved. There is no doubt that it was a major commission, equalled by its dimensions: the bust is one metre high and 80 cm wide: it is larger than life, and in Venetian sculpture of the time it is not easy to find a term of comparison from this point of view. Which therefore makes the choice of sculpting such a remarkable piece even more significant, obtained as it was from a single block, while resorting to this singular solution of an almost high-relief bust.

Bonazza’s inventive intelligence emerges clearly if we look at the Bacchus first from the front and then from the left, since the face of the god reveals itself in a very different way, and it would seem that the sculptor had foreseen both one point of view and the other. And again, if we look at it from the right, even if at that point the Bacchus tends to become elusive, the maniacal care with which the ear has been sculpted captures all our attention. From this angle, moreover, it is clear that, in order to sculpt his Bacchus, Bonazza profited from his experience in relief portraiture: the comparison with the aforementioned Attila and Ezzelino in the Padua museum is illuminating in this respect.

In the Bacchus, the rendering of the eyes is also extraordinary, beneath arched eyebrows blown out of proportion, yet at the same time perfectly coherent and in accordance with the pronounced cheekbones, and the almost goat-like nose: everything is aimed at suggesting and emphasizing the jovial character, while also bordering on the feral, in this divinity linked to the cycle of Nature, whose Panism Bonazza masterfully expresses. Effects obtained through an admirable technical virtuosity, capable of almost letting us forget the hardness of the marble, rendered ductile like wax to fully yield the exuberant vitality of this figure.

Venice between the 17th and 18th centuries offered the most fertile cultural background for the appreciation of such an original and excessive language, and some of the busts depicting Heraclitus weeping demonstrate this unequivocally, but it would seem that Le Court’s followers, starting with Orazio Marinali and Michele Ongaro, were more at ease with the expression of pain and drama; and so in some pairs of Heraclitus and Democritus, even the latter’s laughter ends up resembling a grimace of pain (see those in the Civic Museum of Padua)[13]while Le Court himself, in his beautiful bust of Democritus in the Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico, had not portrayed the philosopher’s laughter nearly as effectively as his companion’s tears. And even in contemporary Tenebrist painting, there is an abundance of subjects, also rare kinds, of intense drama, however there is a lack of episodes full of merriness and joie de vivre. For Bonazza, in contrast, the situation was very different, indeed diametrically opposed. Semenzato, in his essential study of 1959, had already emphasized on several occasions the intimately good-natured character of so much of the sculptor’s production, who always tended to invest his subjects with that charge of positivity that even seems to emerge from the profiles of the barbarian kings, as if they had been deliberately reduced to cartoons to smile over.

And it is always significant, and consistent with what has been said so far, that Bonazza instead tackled a completely new genre for Venetian (and not only Venetian) sculpture, that of the so-called “pagoda figures”, i.e., figurines of crouching, laughing, Chinese people. The sculptor’s first, most famous and remarkable pagoda figures, in the University Library of Padua (Figg. 26, 27, 29, 31, 33), were correctly referred to their author, purely on a stylistic basis, by Semenzato. [14]

The pagoda figures of Bonazza were always sculptures for private clients and we have dealt with them here because, just like this bust, they are some of the most convincing proofs of Bonazza’s originality. An artist not only of great inspiration and technical virtuosity, but also a brilliant innovator.

And again because the coarse leer of these figures, sometimes caught in the act of making the vulgar gesture of the “fig sign”, [15] well matches the expression of our Bacchus, while at the same time also proving useful to frame even better the register adopted by Bonazza in the bust being presented here. Although he wanted to exaggerate the caricatural deformation, Giovanni did not make his Bacchus an almost grotesque figure, of a popular, low genre, miraculously managing to preserve his heroism, underscored by his size.

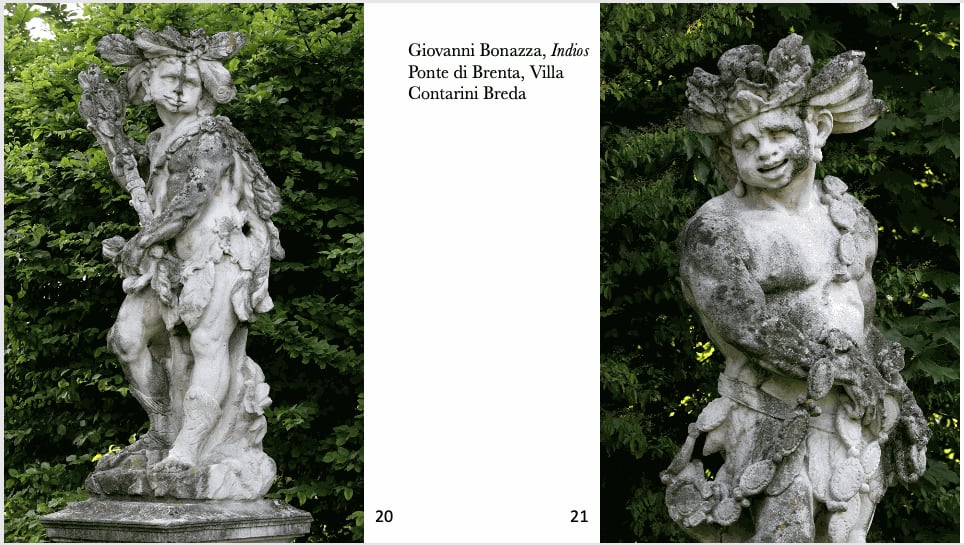

Meanwhile, and still in relation to the Bacchus, we cannot fail to mention yet another of Bonazza’s major works, and one of his most representative, namely, the cycle of statues of Indians and other exotic figures, in stone, from the garden of Villa Contarini-Guastavillani [now Breda] in Ponte di Brenta (Figg. 20, 21, 23, 25), attributed to the sculptor by Semenzato, who gave a description that was also the result of the enthusiasm born from such an exceptional discovery. A description which, in many ways, could be borrowed to talk about the Bacchus presented here:

“This is truly his most fantastic creation... Their faces show on the one hand a sly lunar roundness and, on the other, an exuberant solar liveliness. Their crowns of feathers become manes of rays, every face of the Indians distorted and drunk with wild disorder, of an irrepressible good humour, could become the symbol of a good-natured rustic sun-god. The most unbridled hilarity swells the grimaces of the cheeks and limbs, dilates the laughter, becomes the ferment of their exuberance.”[16]

These statues were dated by Semenzato to 1714, since in that year Bonazza was documented as being at work on the Saint Mark and Saint Daniel in the parish church of the same town.[17] In reality, we cannot be certain of the relationship between the two commissions, and we can perhaps only reconfirm that this cycle of statues belongs to the happiest moment of the sculptor’s production.

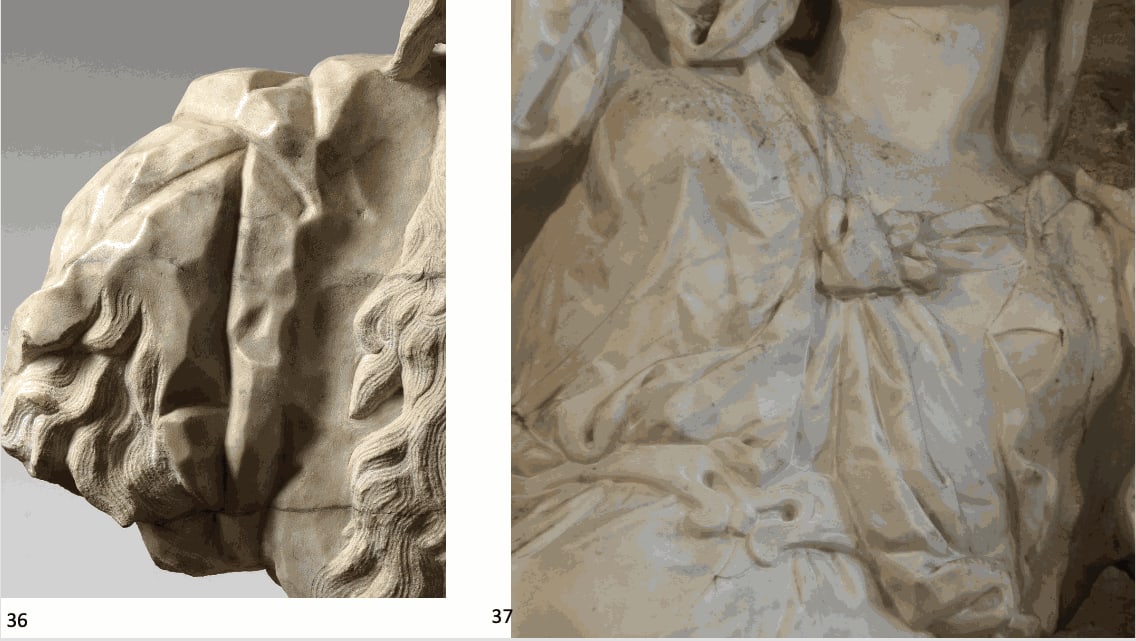

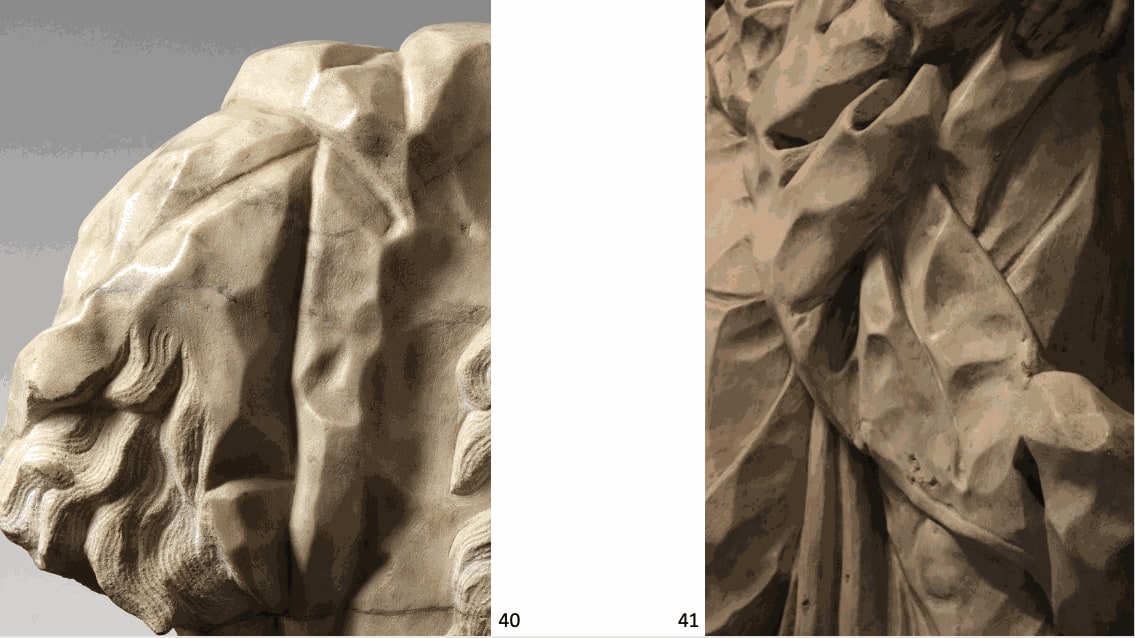

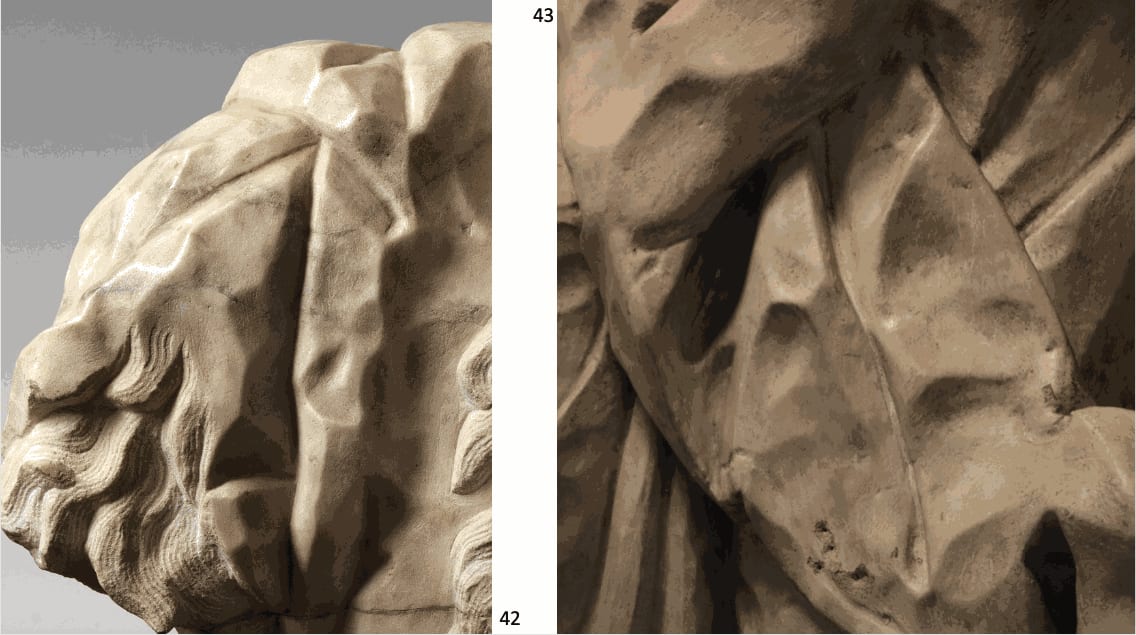

As for the chronological placing of our Bacchus, here we would like to refer this exceptional masterpiece to the years of Bonazza’s early maturity, roughly between the end of the 1680s and 1700, that is, before his work, especially with regard to the drapery, began to betray the influence of Parodi (when, at the end of the 17th century, he moved to Padua, where this Genoese artist had been working for a long time). In our marble, in fact, the albeit paltry piece of drapery on the right shoulder unequivocally betrays a direct relationship with Bonazza’s first important masterpiece, the Monument to Girolamo Garzoni in the Frari Basilica (1689) (Figg. 34, 35, 37).

Truly eloquent, again because of this characteristic of the drapery, shattered as if it had been hammered, is above all the comparison with the Madonna del Carmelo of the Church of Sant’Agnese in Treviso (Figg. 39, 41, 43), “with its crumpled and crackling drapery in a succession of luminous vibrations”, dated by Guerriero to the early 1580s.[18]

Confirming an early dating of Bacchus also seem to be the eyes with their pupils deeply carved with a drill, just as can also be seen in a significant work by Michele Ongaro (an important artist for Bonazza’s training), namely, the marbles of the Vendramin Chapel in the Basilica of San Pietro di Castello, Venice, in this case the relief of Paul V Placing the Cardinal’s Hat on Francesco Vendramin. Only in one other instance, as already mentioned, would it seem that Bonazza treated the eyes of his statues in this way (namely, the busts of Palazzo Roncali in Rovigo). It is interesting that in the last quarter of the 17th century we can find another fitting match in this regard, namely the figures of Telamons on the façade of the Church of the Ospedaletto, a lecourtian worksite (1670-1674). As already mentioned, Bonazza later tamed the capricious nature of his drapery, as can already be seen in the stucco statues of the Basilica of San Bellino (1700), and then above all in the stringy fabrics of the allegorical figures of the aforementioned Valier Monument.

In addition to the caricatural accent and technical virtuosity, another element, as already mentioned, characterizes this Bust of Bacchus, namely its exceptional size, larger than life. And on several occasions Bonazza tackled the “colossal” register (from the “double statues” in the garden of Villa Pisani in Stra, to the almost as imposing complex of statues and colossi for the garden of Villa Manin in Passariano).[19]

The colossal scale had also been adopted by the sculptor in the field of sculpture for ecclesiastical destinations: the cycle of fifteen statues in soft stone for the Archpriest Church of Candiana, proudly signed and dated by the author (BONAZZA F. ANNO DNI MDCCXXII) are much larger than life-size.[20] Then we must also mention the two colossal busts of Petrarch and Laura in the garden of Villa Rosa, Braga Rosa in Tramonte di Teolo (Padua), perhaps to be dated before 1700, and which have been attributed to Bonazza on the basis of a stylistic reading. [21]

And finally, a comparison with painting, with Pietro Della Vecchia, and therefore a useful element to frame Bacchus in the fully Baroque Serenissima of the 17th century: four colossal Character Heads which have been attributed to this great exponent of the most capricious and bizarre vein of Venetian painting (200 x 145 cm; Vicenza, Civic Museum)[22] which again offer a compelling parallel with Bonazza’s work, from the medallion with Attila to the Bacchus itself. These Character Heads by Della Vecchia were not brought to the attention of scholars until 2004, and confirm that if on the one hand our knowledge of the Venetian Baroque is now very advanced, on the other, much remains to be done, much remains to be discovered. We still know little about this taste which had developed in the lagoon, already by the 17th century, for a colossal size of paintings and sculptures, and their grotesque or caricatural characteristics.

What is certain is that Bonazza was an unparalleled interpreter of this taste, and this Bacchus is, to date, the most representative work known.

- Andrea Bacchi

NOTES:

*This text will be published in an extended form in [the journal] “Nuovi Studi”, 28, XXIX, 2024.

[1] Rudolf Wittkower, Art and architecture in Italy 1600 to 1750, Harmondsowrth 1958, p. 299.

[2] Andrea Bacchi, «Le cose più belle e principali nelle chiese di Venezia sono opere sue»: Giusto Le Court a Santa Maria della Salute (e altrove), in “Nuovi Studi”, XI, 2006, 12, p. 156.

[3] Simone Guerriero, Per l’attività padovana di Giovanni Bonazza e del suo “valente discepolo” Francesco Bertos, in “Bollettino del Museo Civico di Padova”, XCI, 2002, pp. 105-120.

[4] One exception in this sense is the San Girolamo penitente in the Biblioteca Universitaria of Padua, signed GIO BONAZZA, Camillo Semenzato, Due “cinesi” del Bonazza, in “Arte figurativa”, VIII, 1960, p. 67.

[5] Francesca Barea Toscan, Pietro Donà committente d’artisti nel castello di Montegalda, in “Arte veneta”, LIII, 1998, p.172; quattro personificazioni dei mesi di Marzo, Aprile, Maggio e Giugno; Sergej O. Androsov, Pietro il Grande, collezionista d’arte veneta, Venice 1999, pp. 216-217, cats. 35-38.

[6] Camillo Semenzato, Le statue dell’Orto Botanico di Padova, in “Arte veneta”, XXXII, 1978, pp. 397-398 (the scholar reported that two of the four busts both depicted Alaric, but from the inscriptions on the corbels it is clear that one of them actually portrays Totila).

[7] Simone Guerriero, Le alterne fortune dei marmi: busti, teste di carattere e altre “scolture moderne” nelle collezioni veneziane tra Sei e Settecento, in La Scultura Veneta 2002, pp. 73-149.

[8] Camillo Semenzato, Studi su ville venete, in “Arte veneta”, XV, 1961, p. 297; Simone Guerriero, Per un repertorio della scultura veneta del Sei e Settecento, in “Saggi e memorie”, 33, 2009, pp. 207, 226-227.

[9] For the attribution of the two marbles, see Andrea Bacchi, entry in Ospiti al museo: maestri veneti dal XV al XVIII secolo tra conservazione pubblica e privata, exhibition catalogue (Padua, Musei Civici) edited by Davide Banzato, Elisabetta Gastaldi, Padua 2012, pp. 116-117, cats. 31-32.

[10] Simone Guerriero, entry in Dal Medioevo a Canova: sculture dei Musei Civici di Padova dal Trecento all’Ottocento, edited by Davide Banzato, Venice, 2000, pp. 163-166, cats. 90-91.

[11] Monica De Vincenti, entry in Dal Medioevo a Canova 2000, pp. 169-192, cats. 97-172.

[12] The bust comes from a Venetian palace of the Querini family, and it would therefore be natural to link its patronage to the aforementioned Elisabetta Querini, the last true Dogaressa of Venice, who died (it should be remembered) in 1709.

[13] Guerriero 2002 (Le alterne fortune dei marmi...), pp. 84-85

[14] Semenzato 1960, p. 67; the exceptional importance of these small marbles was rightly pointed out by Antonia Nava Cellini in La scultura del Settecento, Turin 1982, pp. 172-173.

[15] Simone Guerriero, Giovanni Bonazza, Pair of Chinese Pagoda Figures, in A taste for sculpture, V, edited by Andrea Bacchi, London 2018, pp. 64-66.

[16] Camillo Semenzato, Giovanni Bonazza, in “Saggi e memorie di storia dell’arte”, 2, 1959, pp. 296-297, 309; again, these are works discussed in his manual of 18th-century sculpture in Italy by Nava Cellini (1982, p. 171).

[17] Semenzato 1959, pp. 295 e 305, 309.

[18] Ibid

[19] Semenzato 1959, pp. 299, 309-310, 313, doc. 8.

[20] Enrico Dal Pozzolo, Pietro Della Vecchia, in Pinacoteca Civica di Vicenza. Dipinti del XVII e XVIII secolo, edited by Elisa Avagnina, Cinisello Balsamo 2004, pp. 127-129.

[21] Monica De Vincenti, Simone Guerriero, Per un Atlante della statuaria veneta da giardino, III, in “Arte Veneta”, LXIV, 2007, p. 291.

[22] Enrico Dal Pozzolo, Pietro Della Vecchia, in Pinacoteca Civica di Vicenza. Dipinti del XVII e XVIII secolo, edited by Elisa Avagnina, Cinisello Balsamo 2004, pp. 127-129.

Join the mailing list

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive all the news about exhibitions, fairs and new acquisitions!