RAYMOND DAUSSY CHERBOURG 1918-CÉZABAT 2009

Provenance

The artist's heirs

Exhibitions

Galerie Alain Blondel, Raymond Daussy, Peintures, 1941 – 1963, Paris, 1984.

Literature

R. Daussy – A. Blondel, Raymond Daussy, Paris, 1984, p. 54

A childhood in Cherbourg in the years immediately following the end of the Great War, in a climate of obvious and understandable melancholy, offered Raymond Daussy only rare moments of leisure, yet the films that he went to see at the cinema every Sunday initiated him to the world of art.

His family moved to Rouen in 1929. He showed little interest in academic subjects at school, but he did begin to develop a marked interest in the observation of nature which prompted him to spend a great deal of time at the Natural Sciences Museum and to admire the accomplishments of such explorers as Nobile, Amundsen, Nungesser and Coli.

He was accepted by the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris at the age of twenty and discovered Italian Early Renaissance painters such as Mantegna, Antonello da Messina and Paolo Uccello in the halls of the Louvre. At the same time he developed a passion for the art of José Gutiérrez Solana and studied Roger de La Fresnaye, but when war broke out he was drafted into the forces and soon captured. Managing to escape, he returned to Paris where he rented a studio in Montmartre and began to get better acquainted with the work of such artists as Altdorfer, Grünewald, Dürer, Crivelli and Friedrich while also showing his own work in the exhibition rooms of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and at the Salon d’Automne.

In 1945 he met Édouard Jaguer and the Surrealists who had continued to paint even during the German occupation. He took an interest in the work of Max Ernst, Lionel Feiniger and Roberto Matta. With the support of Alfred Courmes he presented his first one-man show at the Maison des Beaux-Arts, earning a very flattering critique from Jaguer. In response to an invitation from André Breton, he took part in the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme at the Galerie Maeght in 1947. Certain dissident positions within the group prompted a number of artists to oppose Breton’s vision, and so Daussy, along with Jaguer, Noёl Arnaud and Yves Battistini, contributed to the launch of a magazine entitled Revolutionary Surrealism which laid claim to a new vision of the movement more in keeping with recent historical change and with the events of the war.

Daussy showed his work at an exhibition entitled Prise de Terre at the Galerie Breteau in 1948, yet forced, like Félix Labisse, to take stock of the spread of Abstract Art, and despite the support of René Char and of Yves Bonnefoy, he failed to push through his personal conception of painting. His art continued to be misunderstood, so he decided to move with his wife and daughter to Cébazat in the historical region of Auvergne while continuing to show his work in Paris with the Phase Group led by Jaguer. The Galerie Alain Blondel held a one-man exhibition of his art in 1984, after which Daussy moved into the realm of writing theoretical texts, producing a series of compositions on the computer in the 1990s.

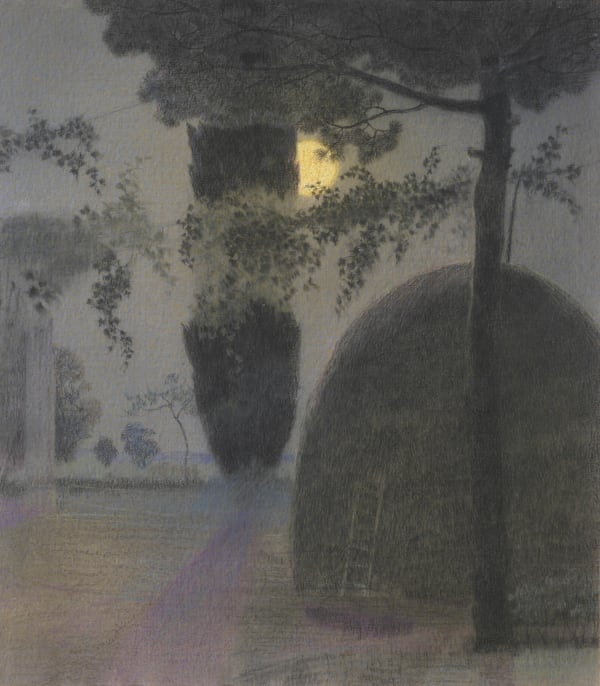

While Daussy’s brief encounter with the Surrealist movement at the end of World War II was to influence his output to a certain extent and to allow him to develop his own take on it, it failed to alter the direction in which his natural bent was driving him. His painterly style gained in poetry and mystery from it, but it remained anchored to daily reality from which he extrapolated the unusual and the bizarre.

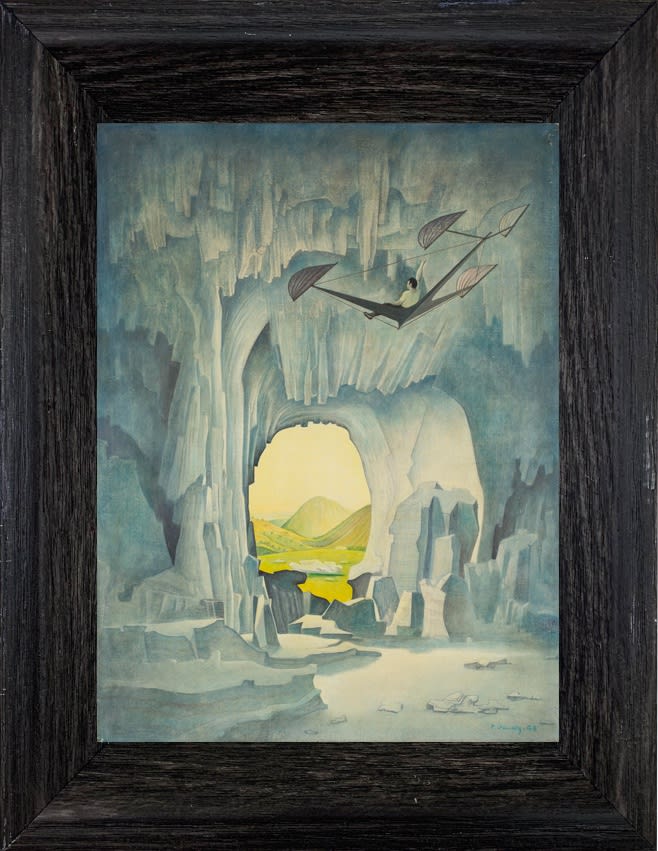

Through his painting, the artist offers us a thoroughly personal depiction of reality thanks to a highly personal conception of space. While we may consider Daussy to have been permeated by the art of the Early Renaissance and of the Italian Renaissance masters in general, he showed no hesitation in turning his back on the traditional rules of perspective in order to subvert his focal points in space and thus trigger a dizzying sense of vertigo. The warped, astonishing and at times even disturbing snapshots that he fixes on the canvas with his smooth brushwork are part and parcel of a broader narrative plot. In freezing the image at a point of precarious balance invariably suspended in the very moment at which everything is about to change, the artist is telling us a story. It is up to us to work out what went before and to guess at what is going to happen next.

Icarus, on board his peculiar plane, attempts to escape the tight space of a cave symbolising the mythological labyrinth built by his father Daedalus for King Minos. Icarus’s precarious position heralds his inevitable downfall. The stone hollow in which he is still imprisoned opens out onto an idyllic natural landscape in a contrast pointing to the vain hope of shedding earthly weight in an existential promise of freedom.

The profound originality of Daussy’s entire output lies in its astonishing power to evoke, to conjure up images in a permanent search for the borderline between the real and the imaginary.

Join the mailing list

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive all the news about exhibitions, fairs and new acquisitions!