ROMANO DAZZI ROME 1905 -FLORENCE 1976

Romano Dazzi, the son of celebrated sculptor Arturo Dazzi, was born in Rome in 1905. Displaying considerable artistic talent from an early age, he held his first one-man show at the Galleria d’Arte Bragaglia in 1919 at the age of only fourteen, presenting 140 drawings for the occasion, and the introduction to the catalogue was penned by Ugo Ojetti, one of the family’s many illustrious friends. The exhibition was surprisingly successful with both the public and the critics, numerous authoritative figures on the art scene of the day considering young Dazzi to be a symbol of the new, younger generation that was coming to maturity in the aftermath of the Great War. The artist’s favourite subjects included primarily combat scenes but he also produced superb portraits of wild animals, despite his knowledge of such beasts being restricted to those in Rome’s zoo, where he would spend days at a time drawing them. Ojetti instantly recognised the boy’s prodigious talent and decided to track his artistic career very closely. Dazzi’s drawings in these early years were still marked by a certain immaturity, which took the shape of a rapid, “expressionistic” style that sat uneasily with Ojetti’s taste for a more tranquil, meditated approach. Ojetti attempted to steer the boy in the direction of a new form of expression, teaching him to govern the exuberance of his creativity with the regulatory strength of style, and indeed the daily control that Ojetti exercised over young Dazzi appeared to bear excellent fruit almost at once, yet the boy was ill at ease with this stylistic tranquillity. The excuse to shake off Ojetti’s constricting supervision came in 1932 when Dazzi was invited by the Italian Government to join Marshal Grazini’s military expedition to Libya in order to record the campaign in a series of drawings. The months that he spent in the desert were to make a deep mark on the artist. The quality of the work he produced in Libya is superb, yet it was not always in keeping with Ojetti’s precepts, and so the relationship between the two began to falter, ending in a bitter separation that generated a feeling of resentment in the critic.

Over the following years Dazzi began to focus on the distinctive motifs of his artistic research that were the rendering of movement, unfinished work and the idealisation of form. In Italy, however, such an approach to art was doomed, while the line theorised by Ojetti was to remain a beacon for aesthetic taste for many decades to come.

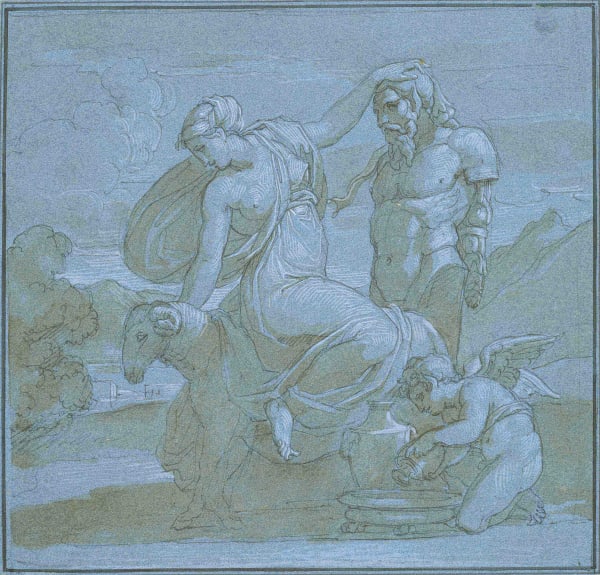

The drawing presented here, which belongs to the series of drawings that Dazzi produced to record the Italian military expeditionary to Libya, testifies to his outstanding illustrative and descriptive skill. His preferred subject matter in Libya ranged from indigenous and Italian soldiers to portraits of Libyans, female figures and figures in the desert. The importance of the drawings that Dazzi produced during his time in Libya lies not only in their superb intrinsic artistic quality but also in the profound impact that the whole experience had on the young man’s artistic career and personal life.

Join the mailing list

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive all the news about exhibitions, fairs and new acquisitions!