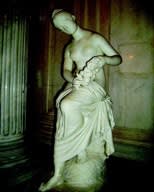

LUIGI BIENAIMÉ CARRARA 1795 -ROME 1878

SOLD

Further images

Provenance

Yeaton Pevery, near Shrewsbury, former home of the Wakeman family; Rome, Galleria Francesca Antonacci; Milan, Private Collection.

Exhibitions

Camuccini Finelli Bienaimé, Protagonisti del classicismo a Roma nell’Ottocento, Galleria Francesca Antonacci, Rome 2003; Equilibrium, exhibition curated by Stefania Ricci e Sergio Risaliti, Florence Museo Salvatore Ferragamo, 19 June 2014 - 12 April 2015; Arte e Vino, exhibition curated by di Annalisa Scarpa e Nicola Spinosa, Verona Palazzo della Gran Guardia, 11 April - 16 August 2015.

Literature

A.M. Ricci, Sculture di Luigi Bienaimé da Carrara, Rome 1838;

Hawks Le Grice, Walks through the studii of the sculptors at Rome with a brief historical and critical sketch of sculpture, 2 voll. Rome 1841;

Jorgen Birkedal Hartmann, La triade italiana del Thorvaldsen. Alcune considerazioni su temi mitologici e cristiani, in “Antologia di Belle Arti”, 1984 nn. 23-24, pp. 90-115;

Bertel Thorvaldsen 1770 – 1844 scultore danese a Roma, (Roma, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, November 1 1989 – January 28 1990), exhibition catalogue edited by Elena di Majo, Bjarne Jørnæs, Stefano Susinno, Rome 1989;

Scultura a Carrara. Ottocento, essays by Mario De Micheli, Gian Lorenzo Mellini, Massimo Bertozzi, artists biographies by Renato Carozzi, Bergamo 1993;

I marmi degli zar. Gli scultori carraresi all’Ermitage e a Peterhof, (Carrara, Accademia di Belle Arti, Massa, Palazzo Ducale, April 13 – June 23 1996) exhibition catalogue edited by Massimo Bertozzi, Milan 1996;

Biarne Jørnæs, Bertel Thorvaldsen la vita e l’opera dello scultore, Roma 1997;

Camuccini Finelli Bienaimé, Protagonisti del classicismo a Roma nell’Ottocento, catalogue of the exhibition curated by Francesca Antonacci, Galleria Francesca Antonacci, Rome 2003;

Stefano Grandesso, Pietro Tenerani (1789 – 1869), Cinisello Balsamo 2003;

Equilibrium, exhibition curated by Stefania Ricci and Sergio Risaliti, Florence Museo Salvatore Ferragamo, 19 June – 12 April 2015, p. 115;

Arte e Vino, exhibition curated by Annalisa Scarpa and Nicola Spinosa, Verona, Palazzo della Gran Guardia, 11 April – 16 August 2015, p. 167.

The present statue is a version of one of the most famous works by this great nineteenth century sculptor. Born in Carrara, in 1795, and son of a possibly Flemish sculptor, Luigi Bienaimé moved to Rome in 1818 when he won the Accademia di Belle Arti of Carrara scholarship prize. As for many other artists coming from several different countries, Rome became Bienaimé’s adoptive town. In the Urbe, they all found the perfect condition for practicing sculpture: they were constantly in contact with the most celebrated models of the classical antiquity; they lived in the 19th century capital of the international art market for the flow of foreign travellers and collectors and, more importantly, they could enjoy the privilege of the mastery of Antonio Canova and Bertel Thorvaldsen – two of the most important sculptors of the age. Bienaimé was first a pupil of the Danish Bertel Thorvaldsen; when the master broke off with his favorite Pietro Tenerani, he then became the Dane main assistant. Despite being employed as chief assistant in Thorvaldsen’s workshop, Bienaimé could also establish himself as an independent artist. As a matter of fact, he often shared with his master very important patrons, such as the Count Giambattista Sommariva, the Duke of Devonshire, the Tsar Nicholas I and the Prince Alessandro Torlonia (On the artist see: Hartmann 1984, Carozzi in Carrara 1993, pp. 172-173). Moreover, he was sought out and, in some cases, befriended by eminent members of the European nobility and the arts.

A. Canova, Baccante con cembali, 1812, marmo Berlino, Bode Museum, Realizzata per Andrei Razumovskij, Ambasciatore russo a Vienna

For example, King Württenburg ordered two bacchantes in 1840 and the Italian poet Angelo Maria Ricci took an especial interest in Bienaimé’s works, ordering several statues from him and being one of the first persons to illustrate Bienaimé’s oeuvre in his Sculture di L. Bienaimé da Carrara of 1838. He never left his adopted city and died there in 1878.

The repertoire of Bienaimé’s creations, always available in a series of plaster models for new marble version, consisted of sacred subjects that recall Thorvaldsen’s works (The Guardian Angel, Baby Saint John), literary subjects that embody the idea of “beauty” (Telemachus), and mostly mythological subjects of “gracious” and “refined” inspiration. However, unlike sculptures from Antiquity, Bienaime’s statues exuded not monumentalism, but softness. This softness, nevertheless, although sentimental, was not overly so as in the work of some of his elders or contemporaries. Through polished variations of subject, which had also been represented by Thorvaldsen, Bienaimé found his own artistic vein, carrying out the same themes with a narrative and sentimental approach that was different from his master’s severe “philosophical” style.

The subject of this statue, the Dancing Bacchante, was also tied to works Thorvaldsen and, before him, Antonio Canova had previously treated, in particular the Dancer sculpted in 1817 by the Dane for Prince Nicolaus Esterhàzy (the model is now at the Thorvaldsen Museum in Copenhagen).

These works shared a common archaeological reference to antique statues’ draperies swelled by the wind such as the Hora at the Uffizi and the Hora that was at that time part of the Ludovisi collection; a reference also echoed in Pietro Tenerani’s Flora (di Majo, Susinno, in Rome 1989, p.322; Grandesso 2003, p.136).

Compared to his master’s works, Bienaimé expressed an original face physiognomy that was not influenced by Thorvaldsen’s oeuvres. Furthermore, he notably amplified the movement by expanding the three-dimensional development of the figures, which turns out to be very different from the typical frontality of the Dane’s sculptures. The “serpentinato” development of the figure within the space, which is similar to works such as the Psyche or the Zephyr, determined the absence of a privileged side, thus benefitting a multitude of viewpoints. This work, intended for a decorative use, was one of the most successful sculptures within Bienaimé’s production.

A drawing of the Dancing Bacchante is recorded on plate XIV of Angelo Maria Ricci’s book on Bienaimé’s oeuvre (Ricci 1838), and is also described in Hawks Le Grice’s Walks through the Studii of the Sculptors of Rome (1841) as standing in Bienaime’s studio as having been executed for Prince Doldenburgh. The most interesting history connected with this statue, however, originates with the Russian expatriate community in Rome, a city that had attracted a number of Russian artists. At this time, a frenetic building activity had taken over the wealthiest inhabitants of St. Petersburg. These new palaces and mansions needed to be decorated, and with this in mind, the upper echelons of Russian society travelled around Europe acquiring objects for their homes. Nicholas I himself entertained ambitions of founding a new Imperial Museum in St. Petersburg. As demonstrated, he was already familiar with the art of Italy; thus, it is not surprising to find him travelling through Italy in 1845. Although he ordered works from many different artists during this trip, Bienaimé was particularly favored by the Tsar when he visited him in his studio. From most sculptors Nicholas I had ordered only one, or possibly two statues; from Bienaimé he commissioned four, including a replica of the Dancing Bacchante. The completed statue was transported to St. Petersburg in 1850 where it was placed in the Winter Palace. Although Nicholas I’s Dancing Bacchante can now be found in the National Gallery at Erevan, another one of larger sizes, signed and dated 1840 and coming from the collection of the princes of Ol’denburgskij’s arrived at the Hermitage in 1923, where it can still be found today. A further smaller version, also in the Hermitage, was probably commissioned by the Prince Boris Yusupov. It is not dated but in the catalogue for the 1996 exhibition I Marmi degli Zar it is argued that it must have been made during the 1840s as a copy of the earlier, larger versions. It is probable that, after the patronage of such illustrious collectors as Prince Doldenburgh and Tsar Nicholas I, the Dancing Bacchante enjoyed great fame and that the present version was executed for another prestigious client sharing similar tastes.

L. Bienaimé, Pastorella, 1854, marmo; San Pietroburgo, Museo Ermitage

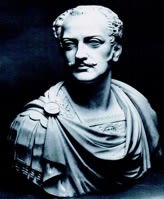

L.Bieneaimé, Busto dello Zar Nicola I, 1846, marmo, San Pietroburgo, Museo Ermitage

Join the mailing list

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive all the news about exhibitions, fairs and new acquisitions!