Prince Pierre TROUBETZKOY

SOLD

Literature

Reference bibliography:

Helene L. Postlethwaite, Some rising Artists, in “The Magazine of Art”, vol. 17, 1894, pp. 113-118; A Russian Painter. A chat with Prince Troubetzkoy, in “The Sketch”, 18 December 1895, p. 417; Julia Magruder, Prince Troubetzkoy’s portrait work, in “Metropolitan Magazine”, vol. V, n. 1-6, 1897, pp. 325-326; Charles L. Borgmeyer, Art of Prince Pierre Troubetzkoy, in “Fine Arts Journal”, vol. XXV, December 1911, n. 6 (part I), pp. 322-335; Charles L. Borgmeyer, Art of Prince Pierre Troubetzkoy, in “Fine Arts Journal”, vol. XXVI, January 1912, n. 1 (part II), pp. 1-21; Charles L. Borgmeyer, Art of Prince Pierre Troubetzkoy, in “Fine Arts Journal”, vol. XXVI, February 1912, n. 2 (part III), pp. 66-83; Robin Simon, The Portrait in Britain and America, Phaidon, Oxford 1987, p. 235

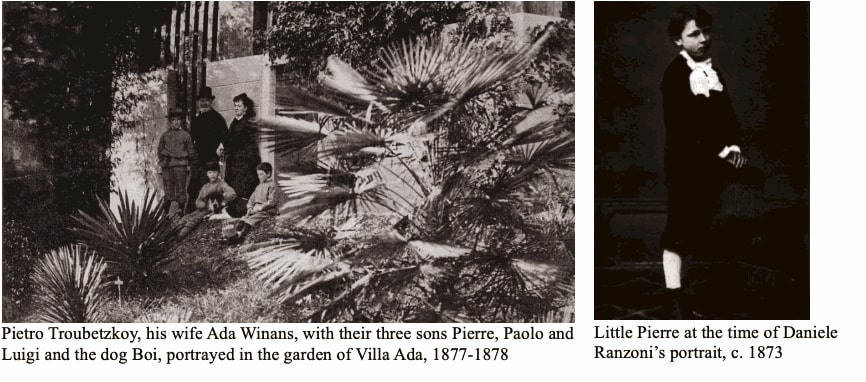

Few lines, but ones which neatly summarize the figure of Pierre Troubetzkoy, a portrait painter of noble birth. The eldest son of the Russian Prince Petr Petrovic (Pietro) Troubetzkoy and an American musician Ada Winans, born in Milan and raised between the Lombard capital and Villa Ada on Lake Maggiore, Pierre received an education befitting his social status. Prince Piotr, a lover of botany – the park and winter garden of Villa Ada were home to rare and precious species of exotic plants – met Ada in Florence. An opera singer who abandoned the stage upon the birth of their first child, she soon turned the lakeside villa into a lively meeting place for musicians, writers and artists: the evenings enlivened by brilliant literary discussions alternating with concerts and the very frequent stays of such artists as Tranquillo Cremona and Daniele Ranzoni. The latter spent long periods there, leaving evidence of them in various works (several views of the villa and the chalet where, from 1890, the family began to live due to some financial difficulties, but also numerous portraits) and providing the first teachings of art and history to the prince’s young sons, whom he portrayed in a famous painting: “the group of three boys in the greenhouse, surrounded by rich exotic palm trees, next to the big damp-nosed dog.”2

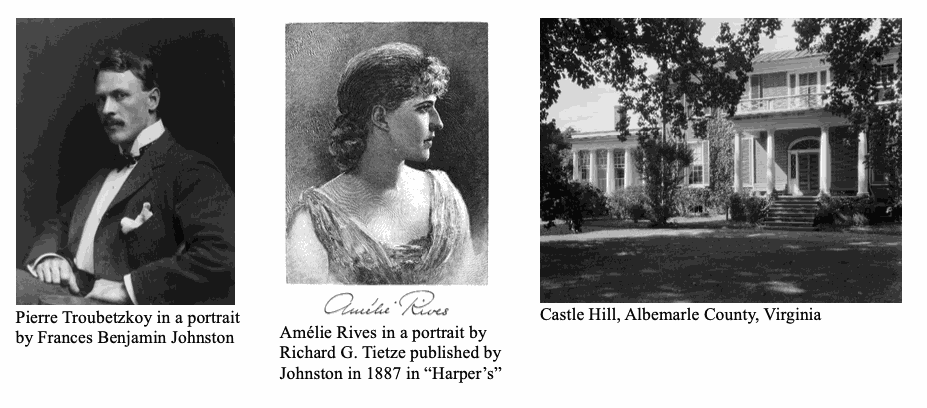

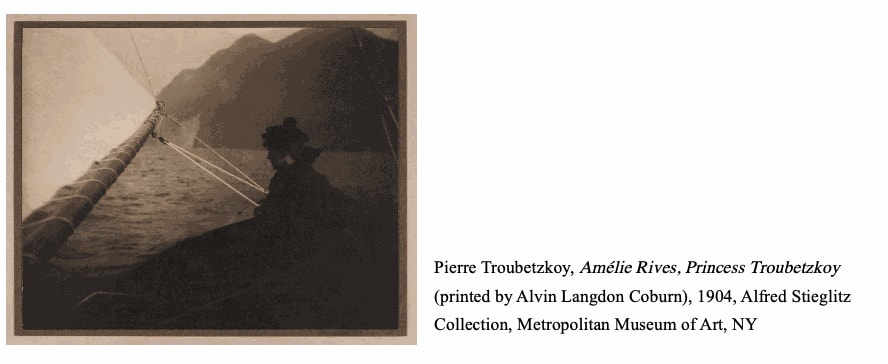

In the summer of 1896, probably through Oscar Wilde, Troubetzkoy made the acquaintance of the brilliant American writer Amélie Rives Chanler, author of the scandalous novel The Quick or the Dead?,8 and at the time married to the American millionaire John Armstrong “Archie” Chanler. The charm of the prince – the photos and testimonies of the time reveal a tall, strapping, good-looking man, “physically something of a giant”,9 with a “charming personality”10 and who combined “[...] the physical appeal of the ‘savage Tartar’ with the romance of his Old World Italian accent and villa”11 – led in the short span of a few weeks to the divorce of the writer from Chanler and, after only four months, Pierre and Amélie were off to the United States to get married in the writer’s paternal home in Castle Hill (Virginia).

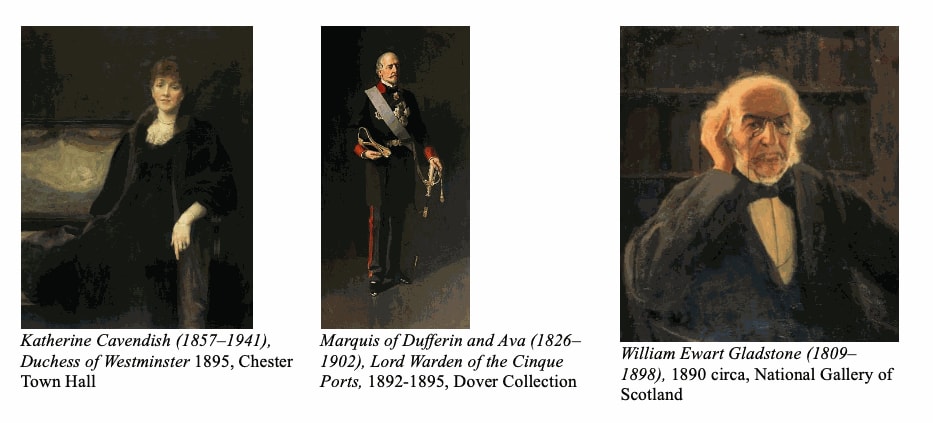

The portrait of the swordsman and his blade with a French handle is conceivably attributable to the artist’s London period or to the first months after his move to the United States (around 1892-1896). The rapid brushwork and the brilliant colour range fully reflect the artist’s Lombard training, accustomed to painting en plein air and still far from that compactness of brushstroke that Troubetzkoy would achieve more fully in the following decade when he would be decisively influenced by the work of one of the most famous portrait painters of the time, the Irishman John Lavery.

The stylistic closeness of this swordsman to such works as Summer Time (a portrait of Dorothy Sylvie Burnett, painted in July 1890) or The Skater (1895), a personal reworking of a similar painting by De Nittis,17 reveal the suggestions of certain styles of Italian painting, oscillating between an Impressionist and vaguely Divisionist lineage as already suggested by the critics: “Prince Troubetzkoy is an Impressionist of an advanced and vigorous type, influenced by Claude Monet, by the Italian Segantini, and others.”18

Paolo Troubetzkoy, Portrait of Pierre Troubetzkoy, 1911-1912

Paul Troubetzkoy, Portrait of Pierre Troubetzkoy 1911-1912 The physical resemblance of the figure to the portrait photos of Pierre, but above all to the portrait made of him by his sculptor brother Paul Troubetzkoy19 finally allows us to reasonably assume that the painting might be a self-portrait of the painter himself. This would also be confirmed by the spontaneity of the posture, decidedly far from the rigorous approach that characterized similar subjects20 and the cut of the composition with the figure caught against the light as in a break during training. Moreover, it is known that Pierre was, among other things, a talented swordsman, as evidenced by a photograph taken by Amélie during the summer of 1894, where the artist “[...] is in fencing gear, his sabre and mask in hand, looking every inch the swashbuckling star that he was”21.

- Agnese Sferrazza.

NOTES:

1 Some Letters from Oscar Wilde to Alfred Douglas 1892-1897, with illustrative Notes by Arthur C. Dennison, Jr. & Harrison Post and an Essay by A.S.W. Rosenbach, San Francisco 1924, p. xxi. For the dating of the letter, see the note on p. xxxvii.

2 Margherita Sarfatti, Daniele Ranzoni, Rome 1935-XIII, p. 132. This work, one of Ranzoni’s best-known, was harshly criticized by Sarfatti, who accused him of “aristocratic affectations, good for astonishing the bourgeoisie” so much so that she also reported an envious joke by the master Cremona: “The dog is made by children, and the children by dogs” (El can l’è faa da fiœu, e i fiœu da can).

3 The work is published in Borgmeyer 1911, p. 322.

4 Artists and their Work, in “Munsey’s Magazine”, vol. XVI, February 1897, no 5, p. 318.

5 Borgmeyer 1911, pp. 327-328.

6 The work was an immediate critical success, as reported in the review on the pages of “The Standard” which emphasized the elegance of the figure “[...] painted with marvellous breadth and dexterity, vigorously drawn, and with a palpable swiftness. The varied contours of the gracefully posed head and neck are indicated with surprising firmness and expressive certainty of line”: see Borgmeyer 1912, no. 1, p. 2.

7 All of Troubetzkoy’s first-person quotations are taken from the interview published in December 1895 in “The Sketch”, cited in the bibliography.

8 Author of more than twenty works of fiction, collections of poetry and the verse drama Herod and Marianne (1889), Amélie Rives achieved enormous success with the public with the novel The Quick or the Dead? published in 1888. This novel, which tells the story of a young widow overwhelmed by erotic passion for her deceased husband’s cousin, was immediately condemned by the critics.

9 Postlethwaite 1894, p. 118.

10 Borgmeyer 1911, p. 335.

11 Donna M. Lucey, Archie and Amélie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age, New York 2006.

12 Artists and their Work, op. cit.

13 Magruder 1897.

14 Among the characters portrayed were the Astors, Roosevelts, and Whitneys. An extensive discussion of American portraits, accompanied by a long list of models portrayed by Troubetzkoy, is in Borgmeyer 1912, no. 2, pp. 73, 75.

15 The volume, which was to be published in 1907 by Grant Richards, saw the light of day the following year with Doubleday, Page & Company. “The Sketch – A Journal of Art and Actuality”, vol. LXIV, 1909.

16 Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection.

17 De Nittis, La lezione di pattinaggio sul ghiaccio, 1875.

18 Borgmeyer 1912, no. 1, p. 14.

19 Paul Troubetzkoy, Portrait of Pierre Troubetzkoy, plaster, 1911-1912 (Landscape Museum, Verbania).

20 See, for example, just to mention two famous examples, Antonio Mancini’s Portrait of Baron Caccamissi as a Swordsman (1901) or Gari Melchers’ The Fencing Master (c. 1900).

21 Lucey 2006.

Join the mailing list

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive all the news about exhibitions, fairs and new acquisitions!