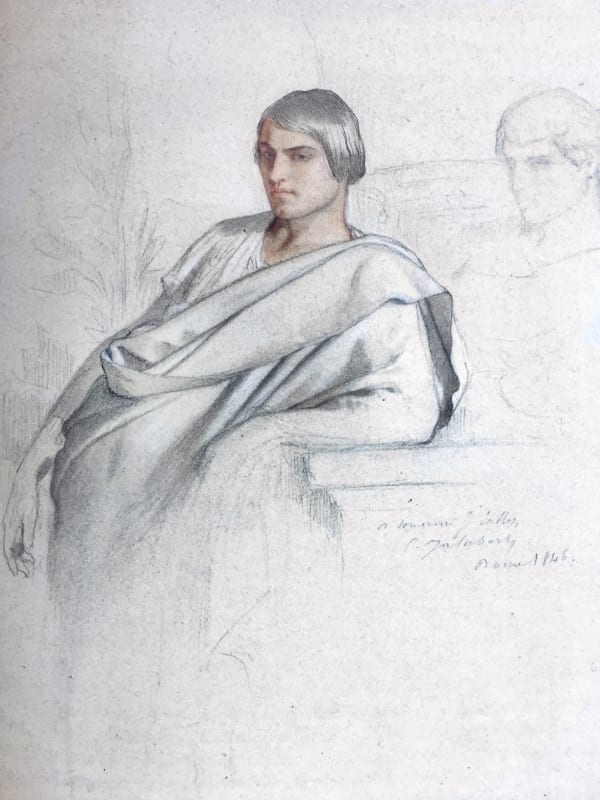

ANDREA APPIANI MILAN, 1754-1817

Mounted on its original cardboard support bearing an original label in the centre with the original legend: "AU COQ HONORÉ, ru du Coq St. – Honoré n°. 7, / chez Alphonse GIROUX / Objets relatif au Dessin , au Lavis et à la Peinture / en géneral ; Bordures dorées , Médallons , jolis articles / de Papeterie et Fourniture des Lycees et des Bureaux."

Old graphite pencil inscription at the top of the mounting support: "Portrait du Prince Camille Borghèse".

42 x 39 x 7 cm (with the frame)

This drawing, in excellent condition and one of the finest products of Appiani’s entire graphic career, reveals the full technical mastery of his draughtsmanship in the skilled use of graphite and temperas in a range of different colours.

The drawing was mounted at an early date on a cardboard support whose label indicates its provenance as being the shop of François-Simon-Alphonse Giroux (1775 – 1848). Giroux was initially a painter in the workshop of Jacques-Louis David but subsequently a renowned merchant of furniture, objets d’art, frames and material for painting and drawing in his premises on the Rue Coq Saint-Honoré in Paris, and his mountings enjoyed an excellent reputation in his day. An old graphite inscription at the top of the card identifies the sitter as Prince Camillo IV Borghese, the husband of Napoleon’s sister Pauline Bonaparte.

The young man is shown in profile, sporting the typical Classical hairstyle with the hair swept forward that was so popular with the members of Napoleon’s entourage, and indeed with Napoleon himself, in the early years of the 19th century. The sitter – who is in fact unlikely to be Camillo Borghese, if we consider such glaring iconographical differences as the absence of the long, thick sideburns with which the Roman prince is invariably portrayed – sports a jacket with fur which bears a striking resemblance to those worn by Napoleon’s Hussars.

The sitter’s facial features, though seen in profile, are very much reminiscent of those of Auguste-Louis Petiet (Rennes, 1784 – Paris, 1858), the son of Claude-Louis Petiet whom the French Government appointed minister extraordinaire in Milan in 1800 with the task of chairing the Special Commission for the Governance of the Cisalpine Republican. An extremely powerful man, Claude-Louis Petiet was portrayed by Appiani between 1800 and 1801 in a splendid full-figure portrait in the company of his two eldest sons, Pierre-François (Rennes, 1782 – Paris, 1835) and the slightly younger Auguste-Louis (Milan, Civica Galleria d’Arte Moderna: fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Portrait of the Minister Claude-Louis Petiet, Chairman of the Special Commission for the Governance of the Cisalpine Republic, with his Sons Auguste Louis and Pierre-François, 1800, oil on canvas; Milan, Galleria d’Arte Moderna.

In this painting – an official portrait celebrating the decisive role played by Claude-Louis in restoring the Cisalpine Republic and at the Battle of Marengo in 1800 – the two sons are depicted in the dress uniform of the Hussars. Auguste-Louis – the figure in the middle ground turning his gaze intently towards the observer – came to Italy in his father’s and Napoleon’s entourage in 1799. Aged only sixteen, he took part in the Battle of Marengo and enrolled in the 10th Hussars with the rank of lieutenant immediately thereafter, serving with that regiment until 1804. He went on to enjoy a spectacularly successful military career, conducted with honour and marked by numerous victories and acts of courage.

Rising to the rank of brigadier general and earning the title of Knight of the Iron Crown, with Napoleon’s defeat and the beginning of the Restoration he was retired and he moved back to Paris for good, taking up the post of head of the historical archives in the Ministry of War. A comparison between the drawing under discussion here and Auguste-Louis’ face as portrayed in Appiani’s splendid painting suggests that we may fairly reliably equate the two sitters on the grounds of the similarities in their features (the lines of their mouth and nose), the treatment of hair and their almost identical age.

Dating the drawing to circa 1800–1 on the strength of a stylistic comparison with other drawings that Appiani is known to have produced in those years lends yet further substance to this hypothesis (fig. 2). Thus Appiani is likely to have made the drawing in Milan immediately after the Austrians were defeated at Marengo on 14 June 1800 and the Napoleonic Cisalpine Republic was restored thereafter, at what was an extremely lively and innovative moment in his artistic career. Sources of the period tell us that no sooner had Napoleon made his triumphal entry into Milan after the Battle of Marengo, than he “sent Carlo Missiaglia’s street servant in search of Appiani. / Appiani soon made his way to court where he found / Napoleon at table, and was embraced and kissed by him. Napoleon asked him whether / he wanted a post, and he replied that he wanted only the post of painter. / Murat [Gioacchino Murat], Vignolle [Martin Vignolle], Berthier [Louis-Alexandre Berthier], and another 12. gen.s [generals] went to see him on the morrow”.

Fig. 2: Portrait of Napoleon, 1801, black pencil and white chalk on light brown paper; Milan, Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, inv. 508.

Aside from the sitter’s identity (which, when all is said and done, is of only secondary importance), this drawing by Appiani, among the most intense of his entire output, is one of the most emblematic testimonials to the aesthetic and semantic change of course which the artist proved capable of impressing on portraiture in the closing years of the 18th century, with Napoleon’s arrival in Milan in 1796. This, in an effort to meet the novel requirements in the field of representation evinced by a totally new political, military and leadership class compared to the recent past and the protagonists of the ancient regime and the old Milanese aristocracy associated with the Habsburgs. Indeed, it was Appiani’s portraits that set the pace of modernity for Italian art in those years.

- Francesco Leone

Join the mailing list

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive all the news about exhibitions, fairs and new acquisitions!