VINCENZO GEMITO NAPLES, 1852-1929

Provenance

Rome, private collection

Literature

Salvatore Di Giacomo, Vincenzo Gemito. La vita e l’opera, Minozzi, Naples 1905.

Marina Miraglia, Giorgio Sommer. Un tedesco in Italia in Un viaggio fra Mito e Realtà. Giorgio Sommer fotografo in Italia 1857-1891, exhibition catalogue by M. Miraglia, U. Pohlman, Rome, Palazzo Braschi 5 December 1992-10 January 1993, Edizioni Carte Segrete 1992, pp. 28-29.

Gianna Piantoni, factsheet of Acquaiolo by Vincenzo Gemito, in Italie 1880-1910. Arte alla prova della modernità, exhibition catalogue by G. Piantoni, A. Pingeot, Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, 22 December 2000-11 March 2001; Paris, Musée d’Orsay, 9 April 2001-15 July 2001; Umberto Allemandi & C., Turin 2000, pp. 103-104.

Maria Antonietta De Marinis, Gemito. Una rivoluzione in scultura, in Da De Nittis a Gemito. I napoletani a Parigi negli anni dell’Impressionismo, exhibition catalogue by L. Martorelli, F. Mazzocca, Naples, Gallerie d’Italia, Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano, 6 December 2017-8 April 2018, Sagep, Genoa 2017, pp. 168-169.

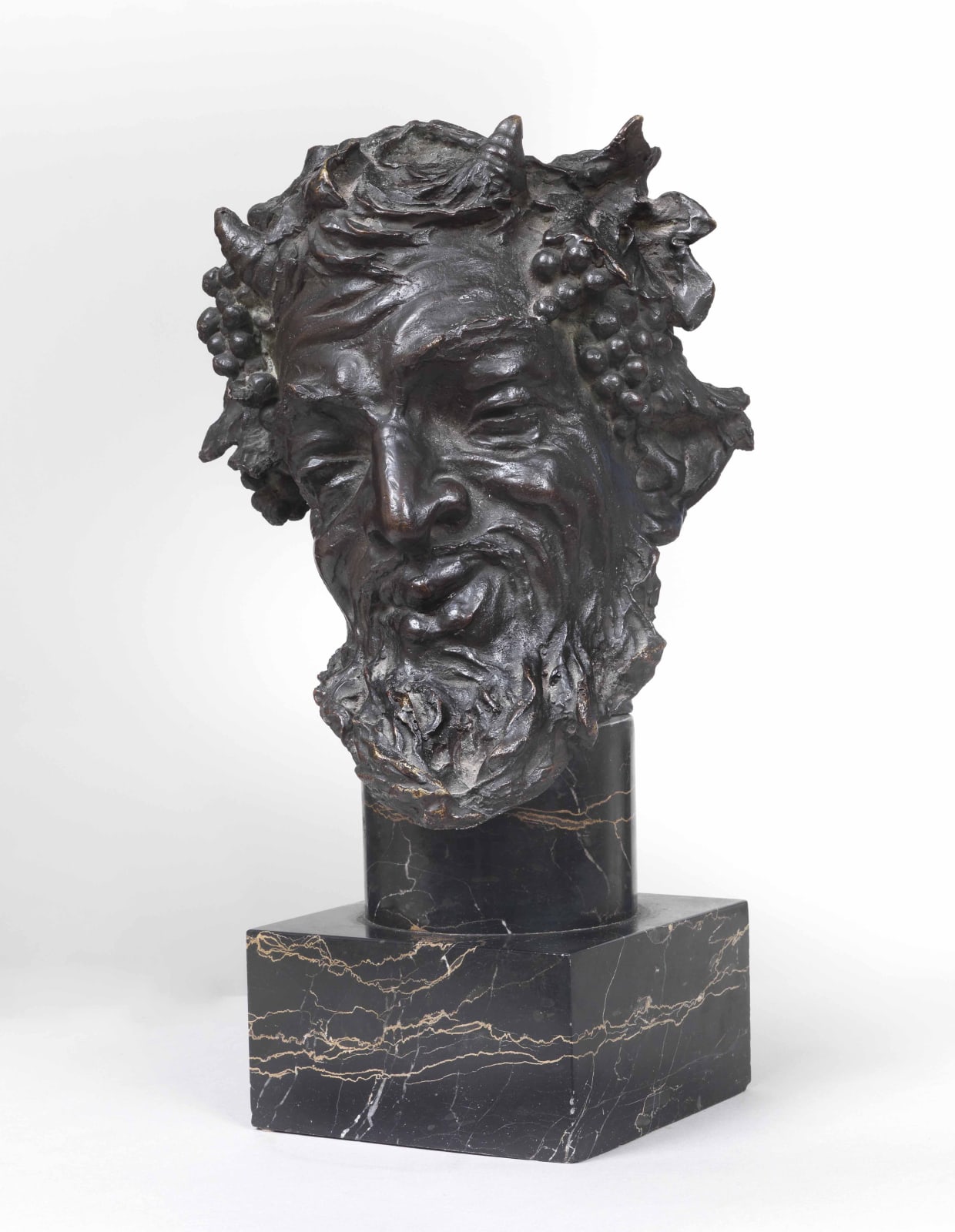

The Head of a Satyr under discussion here, signed by the sculptor bottom left, is a free revisitation of the Drunken Silenus type now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples. The extremely sensitive modelling of the figure’s facial features, marked in an almost expressionistic manner to convey the idea of drunkenness, the creased forehead, the eyes half-closed and reduced to virtual slits, the half-open, swollen lips and even the inclination of the head with its two small goat’s horns hinting at the figure’s loss of balance due to the euphoria induced by the copious imbibing of wine, all form part of a personal interpretation of the theme of Dionysiac transportation of the theriomorphous figure of the Satyr or Silenus, offered by Classical statuary and furnishings.

In this connection, it is worth mentioning that a large part of Gemito’s youthful career was devoted to the reproduction of Classical bronze sculptures, albeit identifying in full with the revisitation of Classical sculpture from both a technical and a formal viewpoint. Thanks to funding offered to him by Belgian Baron Oscar Du Mesnil, Gemito was able to open his own foundry in the Mergellina neighbourhood of Naples in 1883, while the Fonderia Laganà of Naples took over from the Fonderia Gemito in 1886.

In the Head of a Drunken Satyr under discussion here, the face with its marks and its highlights expresses an intensity of feeling bordering at once on pain and on pleasure, its distorted features conveying an image that combines mirth with pathos. Even the beard and the dishevelled hair allude to the emanation of vibrant, sensual energy, while the underlying movement of the facial surfaces and grape-wreathed locks, in their ruffled and unkempt plasticity, is capable of conjuring up echoes of 17th century painting.

Join the mailing list

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive all the news about exhibitions, fairs and new acquisitions!